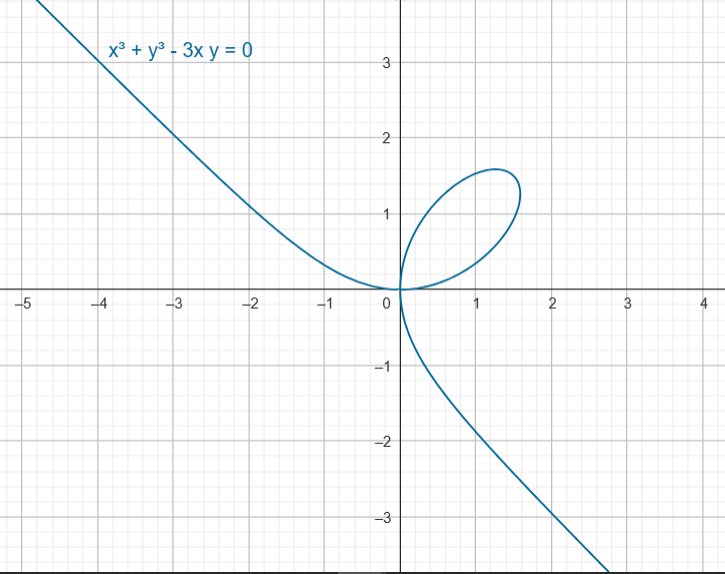

El teorema de la función implícita se usa para determinar si el conjunto de soluciones de un sistema de ecuaciones es una curva suave o una superficie suave o una variedad suave.

Una ecuación con dos variables

$f (x, y) = 0$

$f^{-1} (0) = \big\{ (x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \big| f (x, y) = 0 \big\}$ conjunto de nivel.

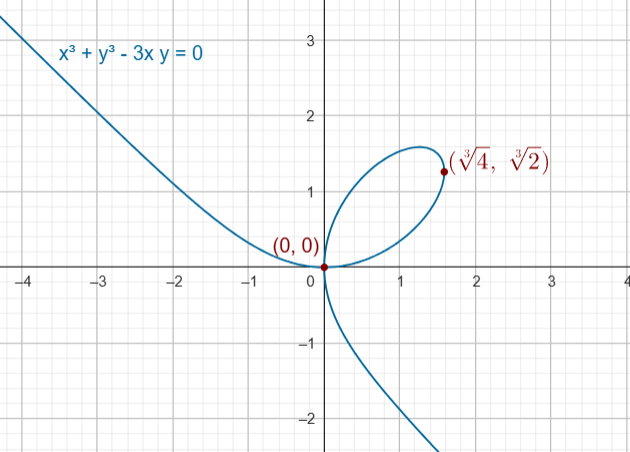

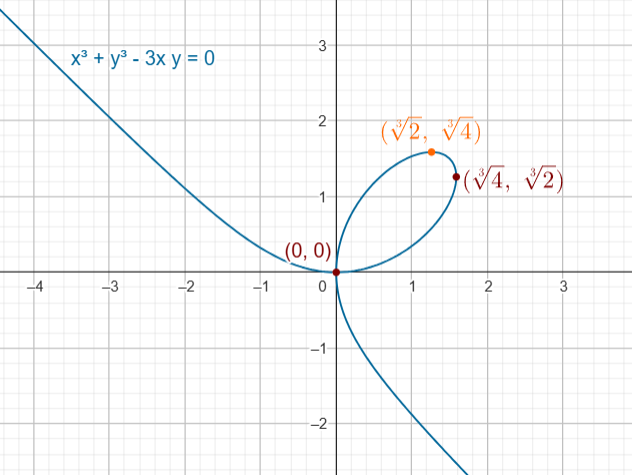

Supongamos que conocemos un punto en $f^{-1}(0)$. Las posibilidades para este conjunto de nivel son:

*) Podría ser un punto,

**) podría ser una o varias curvas que se cruzan, o

***) podría ser una curva con picos.

Para que sea una curva sin picos se debe cumplir las siguientes condiciones:

$f : \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R} $ de clase $\mathcal{C}^1$, $f^{-1} (0) \neq \emptyset$

$\nabla f (p) \neq \vec{0}$, para todo $p \in f^{-1} (0)$

Entonces, $f^{-1} (0)$ es una curva suave sin autointersecciones.

Si $\nabla f (p) \neq \vec{0}$, entonces

a) $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} (p) \neq 0$ entonces existe una función $g$ tal que, cerca de $p$, $f^{-1} (0)$ es la gráfica de $x = g (y)$; o

b) $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} (p) \neq 0$ entonces existe una función $h$ tal que, cerca de $p$, $f^{-1} (0)$ es la gráfica de $y = h (x)$

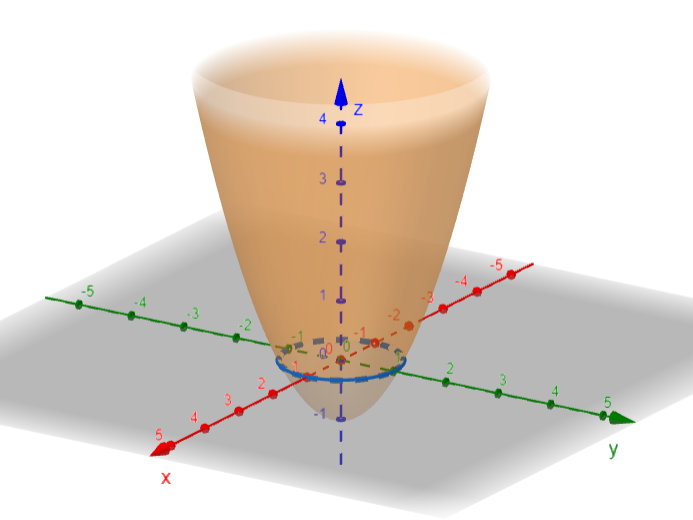

Una ecuación con tres variables

$f (x, y, z) = 0$

$f^{-1} (0) = \big\{ (x, y, z) \in \mathbb{R}^3 \big| f (x, y) = 0 \big\}$ conjunto de nivel.

Supongamos que conocemos un punto en $f^{-1}(0)$. Las posibilidades para este conjunto de nivel son:

*) Podría ser un punto,

**) podría ser una o varias superficies que se cruzan, o

***) podría ser una superficie con «pellizcos».

Condiciones

$f^{-1} (0) \neq \emptyset$, con $f : \mathbb{R}^3 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ de clase $\mathbb{C}^1$

$\nabla f (\vec{p}) \neq \vec{0}$ para todo $\vec{p} \in f^{-1} (0) $

Entonces $f^{-1} (0) $ es una superficie suave sin autointersecciones.

Si $\nabla f (\vec{p}) \neq \vec{0}$ entonces:

i) $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} (\vec{p}) \neq 0$ entonces existe $g $ tal que $ x = g (y, z)$

ii) $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} (\vec{p}) \neq 0$ entonces existe $h $ tal que $ y = h (x, z)$

iii) $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z} (\vec{p}) \neq 0$ entonces existe $\varphi $ tal que $ z = \varphi (x , y)$

Dos ecuaciones con tres variables

$f (x, y, z) = 0$

$g (x, y, z) = 0$

Supongamos que el conjunto de soluciones es no vacío.

¿Qué podría ser?

*) Podría ser un punto.

**) Podría ser una o varias curvas que se cruzan.

***) Podría ser una curva con picos.

Condición

Sea $F : \mathbb{R}^3 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$ tal que

$F (x, y, z) = \big( f (x, y, z), g (x, y, z) \big)$

El conjunto de soluciones del sistema de ecuaciones

$f (x, y, z) = 0$

$g (x, y, z) = 0$

podemos verlo de dos formas

a) como la intersección de dos conjuntos de nivel

$$ f^{-1} (0) \cap g^{-1} (0)$$

b) como la imagen inversa de $(0,0)$ bajo $ F $, es decir $ F^{-1} (0, 0).$

${}$

Si pedimos que $\nabla f (\vec{p}) \neq \vec{0} $ y que $\nabla g (\vec{p}) \neq \vec{0} $ para todo $\vec{p} \in f^{-1} (0) \cap g^{-1} (0)$, lo único que podemos concluir es que localmente, el conjunto de soluciones es la intersección de dos superficies suaves

$ \nabla f = ( 0, 0, 1) \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; f (x, y, z) = z$

$ \nabla g = ( 2x, \, – \, 2y, \, – \, 1 ) \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; g (x, y, z) = x^2 \, – \, y^2 \, – \, z$

$f^{-1} (0) $ plano $z = 0$

$ g^{-1} (0)$ es la silla $ z = x^2 \, – \, y^2$

En el siguiente enlace, puedes observar las gráficas de $f^{-1} (0) $ y $g^{-1} (0) $, así como su intersección.

https://www.geogebra.org/classic/y8cum2au

En este caso la intersección consiste de dos rectas que se cruzan. Para evitar situaciones como esta necesitamos que

$\nabla f (\vec{p})$ y $\nabla g (\vec{p})$ sean linealmente independientes en todo $ \vec{p} \in f^{-1} (0) \cap g^{-1} (0)$.

La matriz de la diferencial de $F$ en $\vec{p}$ es

$$\begin{pmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z} (\vec{p}) \\ \\ \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial x} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial y} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial z} (\vec{p}) \end{pmatrix}$$

¿Qué condiciones debemos pedir en este caso?

Que los gradientes de $f $ y $g$ sean linealmente independientes.

Equivalentemente, que la matriz tenga rango 2.

Equivalentemente, que al menos un subdeterminante de 2×2 (un menor) sea distinto de CERO. De esta última condición, tenemos tres posibilidades:

a) $\begin{vmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} (\vec{p}) \\ \\ \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial x} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial y} (\vec{p}) \end{vmatrix}\neq 0$

b) $\begin{vmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z} (\vec{p}) \\ \\ \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial x} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial z} (\vec{p}) \end{vmatrix}\neq 0$

c) $\begin{vmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z} (\vec{p}) \\ \\ \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial y} (\vec{p}) & \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial z} (\vec{p}) \end{vmatrix}\neq 0$

Si a) se cumple, entonces

$x = h_1 (z)$

$y = h_2 (z)$

Si b) se cumple, entonces

$x = g_1 (y)$

$z = g_2 (y)$

Si c) se cumple, entonces

$y = \varphi_1 (x)$

$z = \varphi_2 (x)$

Veamos un ejemplo de este tipo.

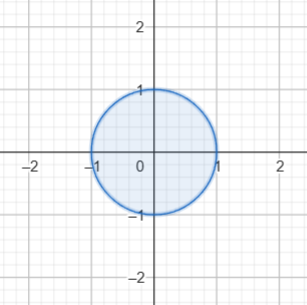

Sea $F (x, y, z) = \big( x^2 + y^2 + z^2 \, – \, 1 , x + y + z \, – \, 1\big)$

$ f (x, y, z) = x^2 + y^2 + z^2 \, – \, 1 = 0$, esfera de radio 1 y centro $(0, 0, 0)$, y

$ g (x, y, z) = x + y + z \, – \, 1 = 0$, plano que pasa por: $(1, 0, 0)$, $(0, 1, 0)$ y $(0, 0, 1)$.

En la siguiente animación puedes observar las gráficas de $f$ y $g$.

https://www.geogebra.org/classic/yvduga9b

La matriz de la diferencial de $F$ en $\vec{p}$ es

$\begin{pmatrix} 2x & 2y & 2z \\ \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}$

Tomemos el punto $( 0, 0 , 1)$, luego analizamos los menores en ese punto:

$\begin{vmatrix} 0 & 0 \\ \\ 1 & 1 \end{vmatrix} = 0$

$\begin{vmatrix} 0 & 2 \\ \\ 1 & 1 \end{vmatrix} = – \, 2 \neq 0 $ entonces $x = g_1 (y) ; z = g_2 (y)$

$\begin{vmatrix} 0 & 2 \\ \\ 1 & 1 \end{vmatrix} = – \, 2 \neq 0 $ entonces $y = \varphi_1 (x) ; z = \varphi_2 (x)$

Luego, puedo elegir cualquiera de estas últimas dos opciones.

En ninguna vecindad del $(0, 0, 1)$ en la circunferencia se parametriza como función de $z$

$$\alpha (z) = \big( x (z), y (z), z \big)$$

$\alpha : (\, – \, \epsilon , \epsilon) \subset \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$

$\alpha (x) = \big( x , \varphi (x), \psi (x) \big)$ entonces $ y = \varphi (x)$ y $ z = \psi (x)$ parametriza una vecindad del conjunto de soluciones cerca del punto $(0, 0, 1)$.

$ \begin{equation*} \left\{ \begin{aligned} x^2 + \varphi (x)^2 + \psi (x)^2 &= 1 \\ \\ x + \varphi (x) + \psi (x) &= 1 \end{aligned} \right. \end{equation*}$

Derivando con respecto a $x$

$ \begin{equation*} \left\{ \begin{aligned} \cancel{2}x + \cancel{2}\varphi (x) + \cancel{2} \psi (x) &= 0 \\ \\ 1 + {\varphi \, }’ (x) + {\psi \, }’ (x) &= 0 \end{aligned} \right. \end{equation*}$

$\begin{pmatrix} \varphi (x) & \psi (x) \\ \\ 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} {\varphi \, }’ (x) \\ \\ {\psi \, }’ (x) \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \, – \, x \\ \\ \, – \, 1 \end{pmatrix}$

entonces en el punto $p = ( 0, 0, 1) = \alpha (0)$

$\varphi (0) = 0$

$\psi (0) = 1$

se tiene que

$\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ \\ 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} {\varphi \, }’ (0) \\ \\ {\psi \, }’ (0) \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ \\ \, – \, 1 \end{pmatrix}$

Entonces

$ \begin{pmatrix} {\varphi \, }’ (0) \\ \\ {\psi \, }’ (0) \end{pmatrix} = {\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ \\ 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}}^{-1} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ \\ \, – \, 1 \end{pmatrix}$

$ \begin{pmatrix} {\varphi \, }’ (0) \\ \\ {\psi \, }’ (0) \end{pmatrix} = {\begin{pmatrix} \, – \, 1 & 1 \\ \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ \\ \, – \, 1 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \, – \, 1 \\ \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}$

Entonces ${\alpha \, }’ (0) = (1, \, – \, 1, 0 )$

Idea general, bajo condiciones adecuadas «genéricas» las propiedades de la derivada (de la diferencial; de la mejor aproximación lineal cerca del punto) se heredan a la función.

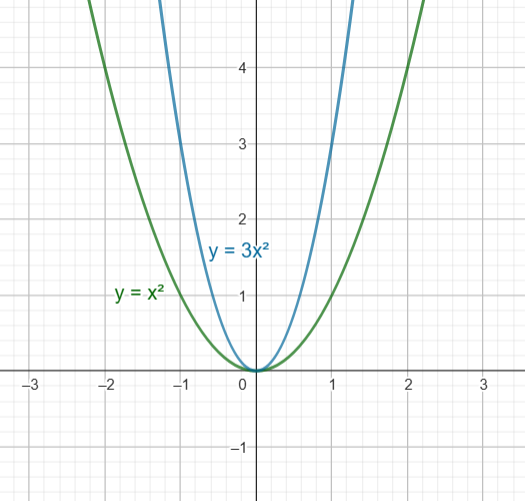

Si $ F : \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$, $F (f, g)$

$d F_p : \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$

$\begin{pmatrix} f_x (\vec{p}) & f_y (\vec{p}) \\ \\ g_x (\vec{p}) & g_y (\vec{p}) \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} h_1 \\ \\ h_2 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} k_1 \\ \\ k_2 \end{pmatrix} $

$d F_p$ es invertible si y sólo si la matriz tiene determinante distinto de cero. Luego $F $ localmente es invertible (cerca de $\vec{p}$ ), quiere decir que podemos despejar las variables independientes.

$ u = f (x, y) \; \; $ entonces $ \; \; x = h (u, v)$

$ v = g (x, y) \; \; $ entonces $ \; \; y = k (u, v)$