Sea $\vec{u} \in \mathbb{R}^2 , \| \vec{u} \| = 1$ un vector unitario.

Sea $(a, b) = \nabla f (x_0, y_0) = \Big( \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0, y_0), \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0, y_0)\Big)$ el gradiente de $f$ en el punto $(x_0, y_0)$, la derivada direccional de $f$ en el punto $(x_0, y_0)$ en la dirección del vector $\vec{u}$ se define como $$\lim_{t \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{f (x_0, y_0) + t \vec{u} \, – \, f (x_0, y_0) }{t}$$ que resulta ser igual a $$\Big( \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0, y_0), \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0, y_0) \Big) \cdot \; \vec{u}$$ $$(a, b) \cdot (\cos \theta, \sin \theta ) = a \cos \theta + b \sin \theta$$

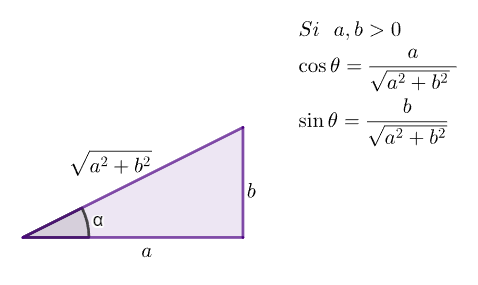

Para cada $\vec{u}$ existe $\theta$ tal que $\vec{u} = ( \cos \theta, \sin \theta).$

¿En qué dirección de $\vec{u}$ se encuentra la mayor derivada direccional?

Para poder calcularla debemos maximizar la función $h ( \theta) = a \cos \theta + b \sin \theta$ donde $h : \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}.$

Entonces

$\begin{align*} h’ ( {\theta}_0) &= – \, a \sin {\theta}_0 + b \cos {\theta}_0 \\ 0 &= – \, a \sin {\theta}_0 + b \cos {\theta}_0 \\ a \sin {\theta}_0 &= b \cos {\theta}_0 \\ \dfrac{b}{a} &= \dfrac{\sin {\theta}_0}{\cos {\theta}_0} \; \; \textit{si $a \neq 0$}\\ \dfrac{b}{a} &= \tan {\theta}_0 \\ {\theta}_0 &= \arctan \Big(\dfrac{b}{a} \Big) \end{align*}$

Entonces tenemos que:

Luego

$h ({\theta}_0) = \dfrac{a^2}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2 }} + \dfrac{b^2}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2 }} = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}$

Además

$${h}^{\prime \prime}(\theta_0) = \, – \, a \cos {\theta}_0 \, – \, b \sin {\theta}_0 = – \, \sqrt{ a^2 + b^2 } < 0$$ por lo que $h$ alcanza un máximo en $\theta_0.$

Un detalle

$$ \theta_1 = \theta_0 + \pi$$

$$ \cos \theta_1 = \cos ( \theta_0 + \pi) = \cos \theta_0 \cos \pi \, – \, \cancel{\sin \theta_0 \sin \pi} = \, – \, \cos \theta_0$$

Análogamente, $\sin \theta_1 = \, – \, \sin \theta_0.$

Luego

$$ \tan \theta_1 = \dfrac{b}{a} = \, – \, \dfrac{\sin \theta_0}{\cos \theta_0} = \tan \theta_0$$

por lo que ${h}^{\prime \prime} (\theta_1) > 0$ y por tanto $h$ alcanza un mínimo, con la hipótesis de $ a \neq 0.$

Si $ a = 0 $ entonces $ h’ (\theta_0) = b \cos \theta_0 = 0.$

Si $ b \neq 0 $ entonces $\cos \theta_0 = 0 $ por lo que $\theta_0 = \dfrac{\pi}{2}$ y $\theta_1 = \dfrac{3 \pi}{2}.$

Por lo que ${h}^{\prime \prime} = \, – \, b \sin \theta$ y por lo tanto ${h}^{\prime \prime} (\theta_0) = \, – \, b$ y ${h}^{\prime \prime} (\theta_1) = b.$

Entonces en $\theta_0$ hay un máximo y en $\theta_1$ hay un mínimo.

En conclusión: El valor máximo de la derivada dirección se alcanza cuando elegimos $$\vec{u} = \dfrac{\nabla f (x_0, y_0)}{ \big\| \nabla f (x_0, y_0) \big\|}$$

Si $ a = 0$ y $ b > 0$ entonces $ \nabla f (x_0, y_0) = (0, b) = b (0, 1).$

El valor máximo de la derivada dirección se alcanza cuando $$\vec{u} = (\cos \theta_0, \sin \theta_0) = ( 1, 0)$$

Si $ a = 0$ y $ b < 0$ entonces $ \nabla f (x_0, y_0) = (0, b) = b (0, \, – \, 1)$ y por tanto $ \Big\| \nabla f (x_0, y_0) \Big\| = \, – \, b.$

Luego ${h}^{\prime \prime} (\theta_1) = b < 0 $ y por tanto $\vec{u} = (\cos \theta_1, \sin \theta_1) = (0, \, – \, 1).$

Entonces $\nabla f (x_0, y_0) = (a, b) = \Big\| \nabla f (x_0, y_0) \Big\|\vec{v}$ con $\| \vec{v} \| = 1$ si $(a, b) \neq (0, 0).$

$(a, b) \cdot \vec{u} = \Big\| \nabla f (x_0, y_0) \Big\| (\vec{v} \cdot \vec{u})$ con $\vec{v}$ y $ \vec{u}$ unitarios pero $\vec{v} \cdot \vec{u} = \dfrac{\cos \alpha}{\| \vec{v}\| \, \| \vec{u}\| } = \cos \alpha$, donde $\alpha$ es el ángulo que forman $\vec{v}$ y $ \vec{u}$, enotnces el máximo valor de $\cos \alpha = 1$ se alcanza cuando $\alpha = 0°$. Por lo tanto, $(a, b) \cdot \vec{u} = \Big\| \nabla f (x_0, y_0) \Big\|.$

Veamos un ejemplo

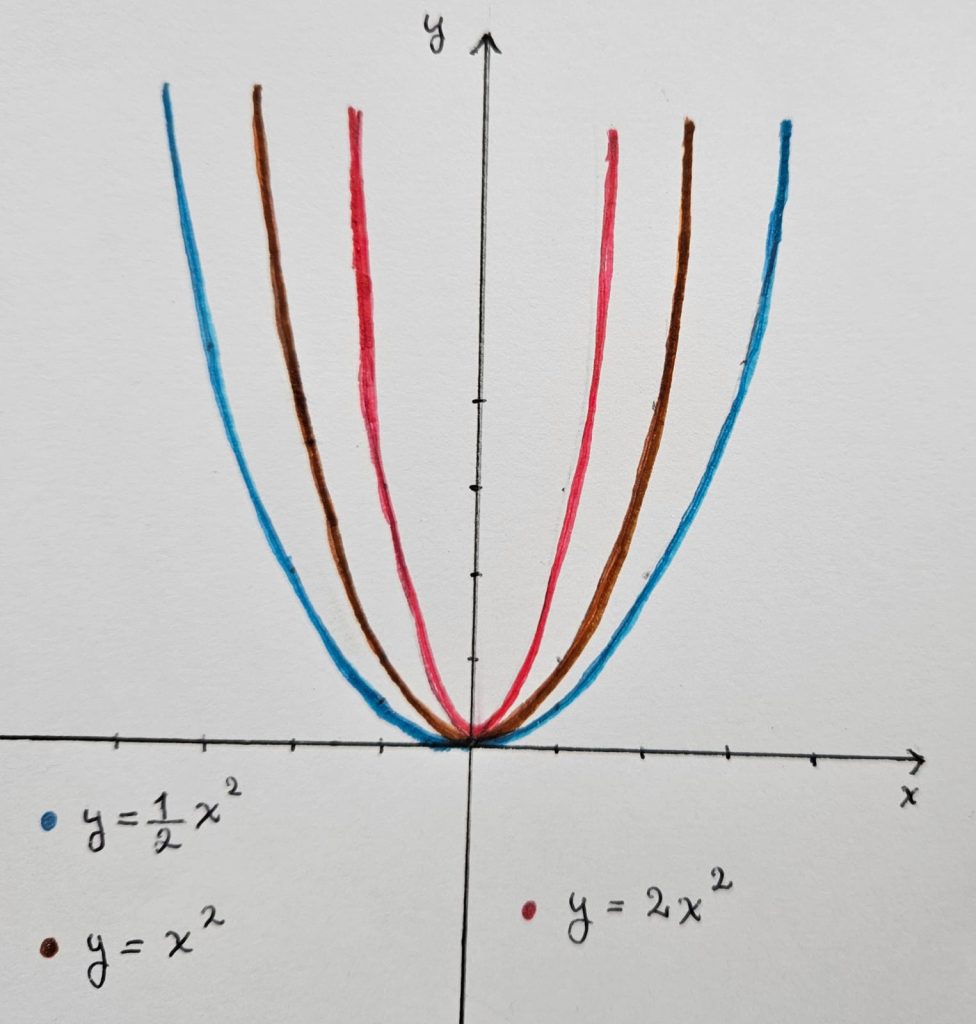

Dada $f (x, y) = x^2 + y^2$ y consideremos el punto $(x_0, y_0) = (2, 3)$

Entonces $ \nabla f (x, y) = ( 2x, 2y ) $

$ \nabla f (x_0, y_0) = (4, 6) $

Luego $x^2 + y^2 = 13$ es una curva de nivel.

En el siguiente enlace puedes observar la gráfica de la función.

https://www.geogebra.org/classic/wk2d4p47

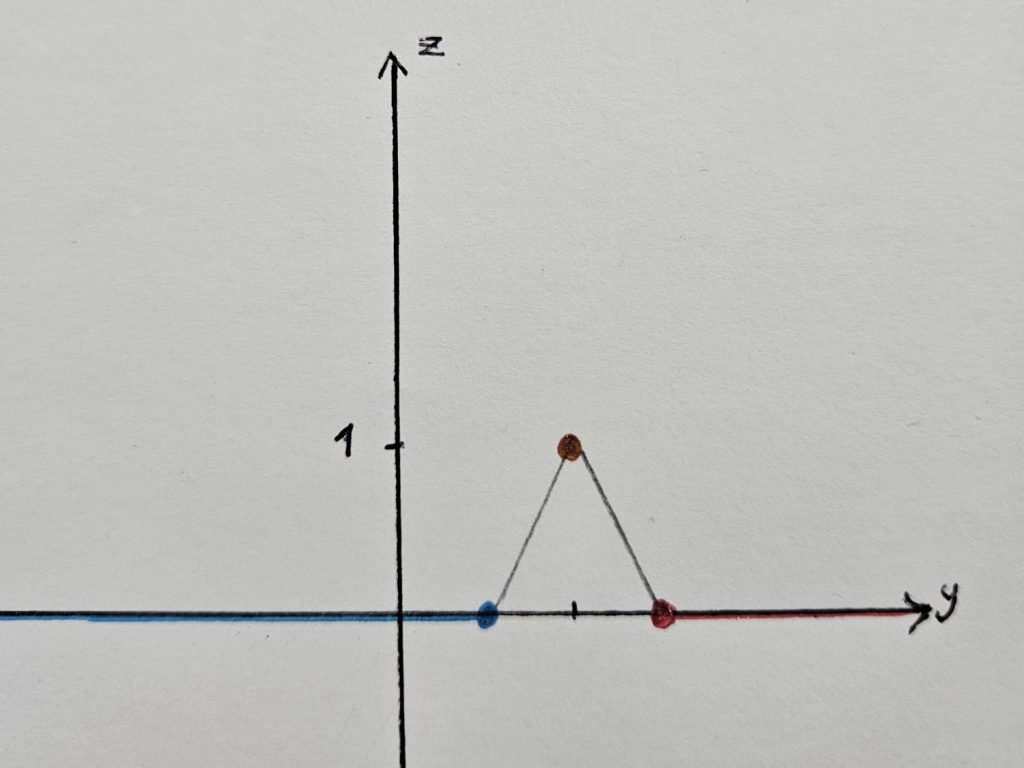

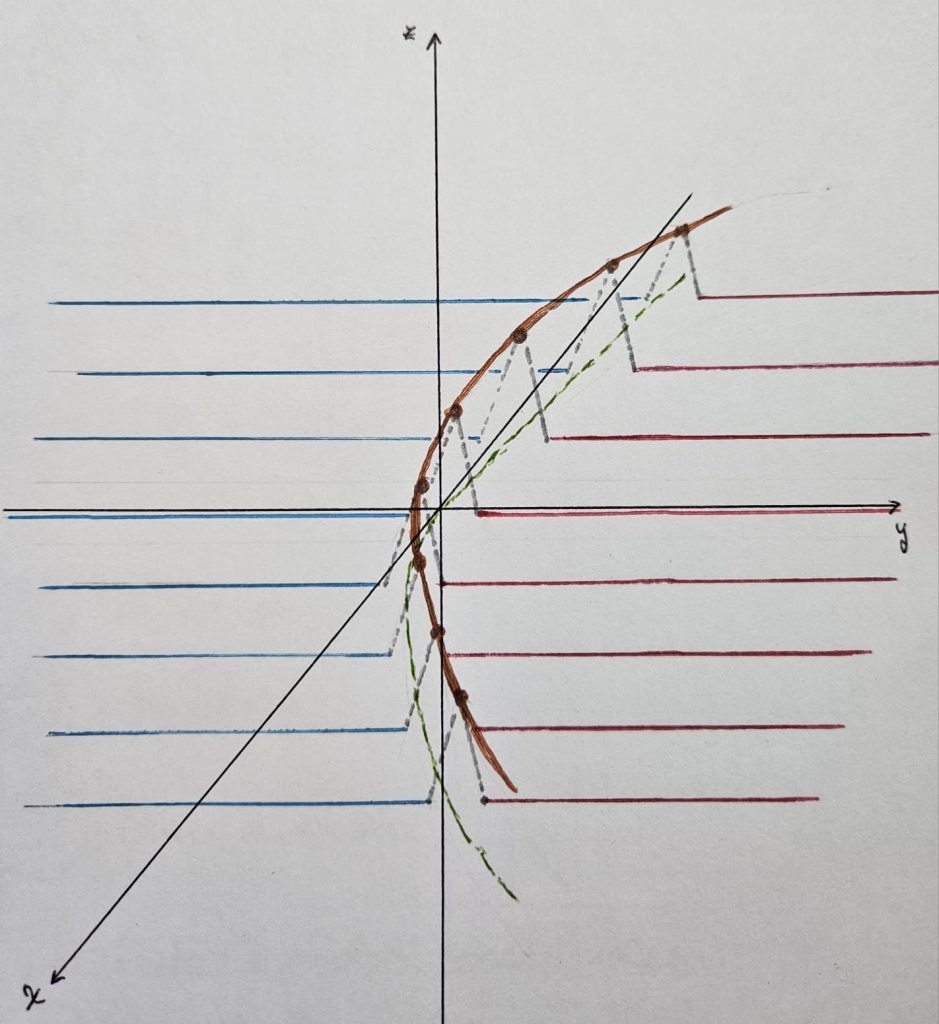

Si consideramos una curva de nivel $\mathcal{c}$ de una función $f : \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ tal que $$\mathcal{C} = \big\{ (x, y) \in A \subseteq \mathbb{R}^2 \big| f (x, y) = \mathcal{c} \big\}$$

Supongamos que podemos parametrizar la curva, es decir, existe $ \alpha : I \subset \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$ tal que $$\alpha (t) = \Big( x (t), y (t) \Big)$$ y además $\alpha (t) \in \mathcal{C} \; \forall \, t$

Luego $f \Big( x (t), y (t) \Big) = \mathcal{c}$ constante, entonces

$h (t) = \big( f \circ \alpha \big) (t) = f \Big( x (t), y (t) \Big) = $constante.

Por lo que $h’ (t) = 0.$

Por la regla de la cadena tenemos que $$h’ (t) = \nabla f \big( \alpha (t) \big) \cdot {\alpha}’ (t) = \nabla f ( x_0, y_0) \cdot {\alpha}’ (t_0) = 0$$

De lo que se concluye que ${\alpha}’ (t_0)$ es ortogonal al gradiente.

${\alpha}’ (t_0) = \Big( \dfrac{dx}{dt} , \dfrac{dy}{dt} \Big)$

$\nabla f (x_0, y_0) = \Big( \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} , \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} \Big)$

Entonces $ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} \dfrac{dx}{dt} \, + \, \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} \dfrac{dy}{dt} = 0$

Despejando

$ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} \dfrac{dx}{dt} = \, – \, \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} \dfrac{dy}{dt} $

Y por tanto

$$ – \, \dfrac{\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}}{\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}} = \dfrac{\dfrac{dy}{dt}}{\dfrac{dx}{d t}}$$

que es la pendiente del vector tangente.