Módulo 2

8. Ecuaciones y factorización

Ejercicios

a. Ecuaciones lineales

Resuelve la ecuación

1. $5(x + 3) – 2 = 3x + 4$

2. $2(3x – 1) + 4 = x + 10$

3. $7x – (2x + 5) = 3x + 9$

4. $\frac{1}{2}(4x – 6) = 3x + 1$

5. $4x + 3 = 2(2x – 1) + 5$

b. Ecuaciones cuadráticas por factorización

Resuelve

1. $x^2 + 5x + 6 = 0$

2. $x^2 – 4 = 0$

3. $3x^2 + 11x + 6 = 0$

4. $4x^2 – 25 = 0$

5. $x^3 – 6x^2 – 4x + 24 = 0$

c. Ecuaciones cuadráticas con fórmula general

Resuelve

1. $x^2 – 7x + 10 = 0$

2. $2x^2 + 5x – 3 = 0$

3. $x^2 + 4x + 5 = 0$

4. $3x^2 – 18x + 5 = 0$

5. $4x^2 – 4x + 1 = 0$

d. Completando el cuadrado

Reescribe completando el cuadrado

1. $x^2 + 10x + 21$

2. $x^2 – 6x + 2$

3. $2x^2 + 8x + 7$

4. $3x^2 + 12x – 1$

5. $x^2 – 4x + 3$

Respuestas modelo

a. Ecuaciones lineales

1. $5(x + 3) – 2 = 3x + 4 \Rightarrow 5x + 15 – 2 = 3x + 4 \Rightarrow 5x + 13 = 3x + 4 \Rightarrow 2x = -9 \Rightarrow x = -\frac{9}{2}$

2. $2(3x – 1) + 4 = x + 10 \Rightarrow 6x – 2 + 4 = x + 10 \Rightarrow 6x + 2 = x + 10 \Rightarrow 5x = 8 \Rightarrow x = \frac{8}{5}$

3. $7x – (2x + 5) = 3x + 9 \Rightarrow 7x – 2x – 5 = 3x + 9 \Rightarrow 5x – 5 = 3x + 9 \Rightarrow 2x = 14 \Rightarrow x = 7$

4. $\frac{1}{2}(4x – 6) = 3x + 1 \Rightarrow 2x – 3 = 3x + 1 \Rightarrow -x = 4 \Rightarrow x = -4$

5. $4x + 3 = 2(2x – 1) + 5 \Rightarrow 4x + 3 = 4x – 2 + 5 \Rightarrow 4x + 3 = 4x + 3 \Rightarrow \text{Identidad: todas las soluciones reales}$

b. Ecuaciones cuadráticas por factorización

1. $x^2 + 5x + 6 = 0 \Rightarrow (x + 2)(x + 3) = 0 \Rightarrow x = -2,, x = -3$

2. $x^2 – 4 = 0 \Rightarrow (x – 2)(x + 2) = 0 \Rightarrow x = 2,, x = -2$

3. $3x^2 + 11x + 6 = 0 \Rightarrow (3x + 2)(x + 3) = 0 \Rightarrow x = -\frac{2}{3},, x = -3$

4. $4x^2 – 25 = 0 \Rightarrow (2x – 5)(2x + 5) = 0 \Rightarrow x = \pm\frac{5}{2}$

5. $x^3 – 6x^2 – 4x + 24 = 0 \Rightarrow (x^2 – 6x) – (4x – 24) = x(x – 6) -4(x – 6) = (x – 4)(x – 6) \Rightarrow x = 4,, x = 6,, x = -1$

c. Ecuaciones cuadráticas con fórmula general

1. $x^2 – 7x + 10 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{7 \pm \sqrt{49 – 40}}{2} = \frac{7 \pm 3}{2} \Rightarrow x = 5,, x = 2$

2. $2x^2 + 5x – 3 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{-5 \pm \sqrt{25 + 24}}{4} = \frac{-5 \pm \sqrt{49}}{4} = \frac{-5 \pm 7}{4} \Rightarrow x = \frac{1}{2},, x = -3$

3. $x^2 + 4x + 5 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{16 – 20}}{2} = \frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{-4}}{2} = \text{no hay soluciones reales}$

4. $3x^2 – 18x + 5 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{18 \pm \sqrt{324 – 60}}{6} = \frac{18 \pm \sqrt{264}}{6} = \frac{18 \pm 2\sqrt{66}}{6} = \frac{3 \pm \sqrt{66}}{3}$

5. $4x^2 – 4x + 1 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{4 \pm \sqrt{(-4)^2 – 4(4)(1)}}{8} = \frac{4 \pm \sqrt{0}}{8} = \frac{1}{2}$

d. Completando el cuadrado

1. $x^2 + 10x + 21 = x^2 + 10x + 25 – 4 = (x + 5)^2 – 4$

2. $x^2 – 6x + 2 = x^2 – 6x + 9 – 7 = (x – 3)^2 – 7$

3. $2x^2 + 8x + 7 = 2(x^2 + 4x + 4 – 4) + 7 = 2(x + 2)^2 – 8 + 7 = 2(x + 2)^2 – 1$

4. $3x^2 + 12x – 1 = 3(x^2 + 4x + 4 – 4) – 1 = 3(x + 2)^2 – 12 – 1 = 3(x + 2)^2 – 13$

5. $x^2 – 4x + 3 = x^2 – 4x + 4 – 1 = (x – 2)^2 – 1$

Problemas

Problema 1. Ecuación en dispersión de sustancias

Una sustancia se dispersa linealmente con el tiempo según la ecuación $C(t) = 5t + 20$, donde $C$ es la concentración y $t$ el tiempo en minutos.

a. ¿Cuánto tiempo pasará hasta que la concentración sea de 45 unidades?

b. ¿En qué instante fue de 35 unidades?

Problema 2. Biomecánica de movimiento muscular

Un músculo genera una fuerza proporcional al cuadrado de su estiramiento. Si la relación es $F = 3x^2 – 12x + 9$, donde $x$ es la distancia estirada:

a. ¿En qué puntos la fuerza es cero?

b. ¿Cuál es el valor mínimo de fuerza?

c. ¿Para qué valor de x se obtiene ese mínimo?

Respuestas modelo

Problema 1. Ecuación en dispersión de sustancias

a. $5t + 20 = 45 \Rightarrow 5t = 25 \Rightarrow t = 5$ minutos

b. $5t + 20 = 35 \Rightarrow 5t = 15 \Rightarrow t = 3$ minutos

Problema 2. Biomecánica de movimiento muscular

a. $3x^2 – 12x + 9 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{12 \pm \sqrt{144 – 108}}{6} = \frac{12 \pm \sqrt{36}}{6} = \frac{12 \pm 6}{6}$

$x = 3,\ x = 1$

b. Completando cuadrados:

$F = 3(x^2 – 4x + 3) = 3(x – 2)^2 – 3$

Mínimo: $F = -3$

c. El mínimo ocurre en $x = 2$

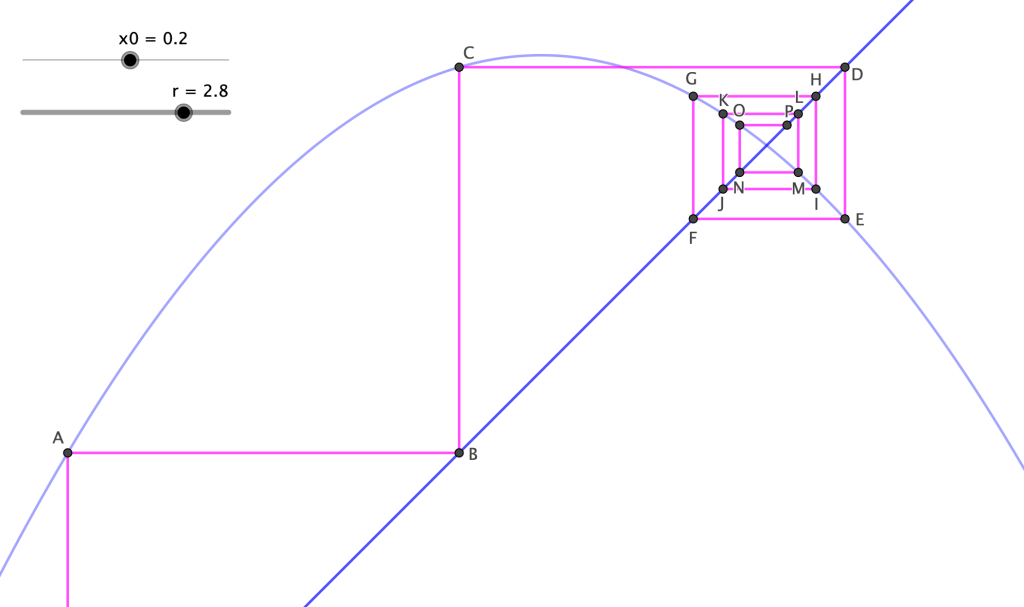

Recursos digitales

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/rw3ahsnu

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/fJp8cgyU

• https://pruebat.org/Aprende/CatCursos/contenidoCurso/44341/

9. Desigualdades

Ejercicios

a. Desigualdades lineales simples

Resuelve las desigualdades y representa gráficamente el resultado

1. $2x + 7 < 15$

2. $5x – 3 \geq 2x + 6$

3. $-4x + 8 < 0$

4. $3 – x > 7$

5. $\frac{1}{2}x + 1 \leq 4$

b. Propiedades de las desigualdades (multiplicación o división negativa)

1. $-2x > 6$

2. $-3x + 1 \leq -5$

3. $-5(x – 1) \geq 15$

c. Desigualdades cuadráticas

1. $x^2 – 4 > 0$

2. $x^2 – x – 6 \leq 0$

3. $x^2 + 2x + 1 \geq 0$

4. $(x – 1)(x + 2) < 0$

5. $x^2 – 5x + 6 \geq 0$

Respuestas modelo

a. Desigualdades lineales simples

1. $2x < 8 \Rightarrow x < 4$

2. $3x \geq 9 \Rightarrow x \geq 3$

3. $-4x < -8 \Rightarrow x > 2$ (cambio de signo)

4. $-x > 4 \Rightarrow x < -4$ (cambio de signo)

5. $\frac{1}{2}x \leq 3 \Rightarrow x \leq 6$

b. Propiedades de las desigualdades (multiplicación o división negativa)

1. $x < -3$

2. $-3x \leq -6 \Rightarrow x \geq 2$

3. $-5x + 5 \geq 15 \Rightarrow -5x \geq 10 \Rightarrow x \leq -2$

c. Desigualdades cuadráticas

1. $x^2 – 4 = (x – 2)(x + 2)$

Solución: $x < -2$ o $x > 2$

2. $(x – 3)(x + 2) \leq 0$

Solución: $-2 \leq x \leq 3$

3. $(x + 1)^2 \geq 0$

Siempre verdadera, solución: todos los reales $\mathbb{R}$

4. Solución entre raíces: $-2 < x < 1$

5. $(x – 2)(x – 3) \geq 0$

Solución: $x \leq 2$ o $x \geq 3$

10. Logaritmos

Ejercicios

a. Definición de logaritmo

Resuelve los siguientes logaritmos

1. $\log_2 8$

2. $\log_5 125$

3. $\log_{10} 100$

4. $\log_3 81$

5. $\log_4 64$

b. Logaritmos comunes y naturales

Resuelve los siguientes logaritmos

1. $\log 1000$

2. $\log 0.01$

3. $\ln e$

4. $\ln 1$

5. $\ln e^5$

c. Propiedades de los logaritmos

1. Simplifica $\log_2 (8 \cdot 4)$

2. Calcula $\log_3 \left( \frac{27}{3} \right)$

3. Evalúa $\log_5 (25^3)$

4. Resuelve $\log_7 1$

5. Resuelve $\log_{10} 10$

d. Cambio de base

1. Calcula $\log_2 100$ usando logaritmos base 10.

2. Calcula $\log_4 20$ usando logaritmos naturales.

3. Expresa $\log_3 81$ como cociente de logaritmos naturales.

4. Calcula $\log_7 49$ usando logaritmos base 10.

5. Escribe una expresión equivalente para $\log_b a$ con base $e$.

Respuestas modelo

a. Definición de logaritmo

1. $\log_2 8 = 3$, porque $2^3 = 8$

2. $\log_5 125 = 3$, porque $5^3 = 125$

3. $\log_{10} 100 = 2$, porque $10^2 = 100$

4. $\log_3 81 = 4$, porque $3^4 = 81$

5. $\log_4 64 = 3$, porque $4^3 = 64$

b. Logaritmos comunes y naturales

1. $\log 1000 = \log_{10} 1000 = 3$

2. $\log 0.01 = \log_{10} 10^{-2} = -2$

3. $\ln e = 1$

4. $\ln 1 = 0$

5. $\ln e^5 = 5 \cdot \ln e = 5$

c. Propiedades de los logaritmos

1. $\log_2 (8 \cdot 4) = \log_2 8 + \log_2 4 = 3 + 2 = 5$

2. $\log_3 \left( \frac{27}{3} \right) = \log_3 27 – \log_3 3 = 3 – 1 = 2$

3. $\log_5 (25^3) = 3 \cdot \log_5 25 = 3 \cdot 2 = 6$

4. $\log_7 1 = 0$

5. $\log_{10} 10 = 1$

d. Cambio de base

1. $\log_2 100 = \frac{\log_{10} 100}{\log_{10} 2} = \frac{2}{0.3010} \approx 6.64$

2. $\log_4 20 = \frac{\ln 20}{\ln 4} \approx \frac{2.9957}{1.3863} \approx 2.16$

3. $\log_3 81 = \frac{\ln 81}{\ln 3} = \frac{4.394}{1.099} \approx 4$

4. $\log_7 49 = \frac{\log 49}{\log 7} = \frac{1.6902}{0.8451} \approx 2$

5. $\log_b a = \frac{\ln a}{\ln b}$

Problemas

Problema 1. Crecimiento poblacional con logaritmos

Una población de bacterias sigue el modelo $P(t) = 200 \cdot e^{0.5t}$, donde $t$ está en horas.

a. ¿Cuántas bacterias habrá después de 4 horas?

b. ¿Cuánto tiempo tardará en alcanzar las 1600 bacterias?

Problema 2. Cálculo del pH

La concentración de iones de hidrógeno en una muestra de agua es de $[H^+] = 3.16 \times 10^{-5}$ mol/L.

a. Calcula el pH de la muestra.

b. ¿Es ácida o básica?

Respuestas modelo

Problema 1. Crecimiento poblacional con logaritmos

a. $P(4) = 200 \cdot e^{0.5 \cdot 4} = 200 \cdot e^2 \approx 200 \cdot 7.389 = 1477.8$

b. $1600 = 200 \cdot e^{0.5t} \Rightarrow 8 = e^{0.5t} \Rightarrow \ln 8 = 0.5t \Rightarrow t = \frac{\ln 8}{0.5} \approx \frac{2.079}{0.5} = 4.158$ horas

Problema 2. Cálculo del pH

a. $\text{pH} = -\log_{10} [H^+] = -\log(3.16 \times 10^{-5}) = -(\log 3.16 + \log 10^{-5}) = -(0.5 – 5) = 4.5$

b. Es una solución ácida porque $\text{pH} < 7$

Recursos digitales

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/kJXr8xKg

11. Iteración

Ejercicios

a. Iteraciones simples con reglas lineales

1. Si $x_0 = 3$ y $x_{n+1} = x_n + 5$, calcula los primeros cinco términos de la sucesión.

2. Si $x_0 = -2$ y $x_{n+1} = x_n + 4$, encuentra $x_1$ hasta $x_5$.

3. Si $x_0 = 10$ y $x_{n+1} = x_n – 3$, calcula los primeros cinco valores.

4. Si $x_0 = 0$ y $x_{n+1} = 2x_n + 1$, determina los primeros cinco términos.

5. Si $x_0 = 5$ y $x_{n+1} = 0.5x_n$, encuentra $x_1$ hasta $x_5$.

b. Iteraciones con crecimiento exponencial o logístico

1. Si $P_0 = 100$ y $P_{n+1} = 2P_n$, halla $P_1$ a $P_5$.

2. Si $P_0 = 80$ y $P_{n+1} = 1.5P_n$, determina los primeros cinco valores.

3. Si $P_0 = 50$ y $P_{n+1} = P_n + 0.2P_n(1 – \frac{P_n}{500})$, encuentra $P_1$ hasta $P_5$.

Respuestas modelo

a. Iteraciones simples con reglas lineales

1. $x_0 = 3$

$x_1 = 3 + 5 = 8$

$x_2 = 8 + 5 = 13$

$x_3 = 13 + 5 = 18$

$x_4 = 18 + 5 = 23$

$x_5 = 23 + 5 = 28$

2. $x_0 = -2$

$x_1 = -2 + 4 = 2$

$x_2 = 2 + 4 = 6$

$x_3 = 6 + 4 = 10$

$x_4 = 10 + 4 = 14$

$x_5 = 14 + 4 = 18$

3. $x_0 = 10$

$x_1 = 10 – 3 = 7$

$x_2 = 7 – 3 = 4$

$x_3 = 4 – 3 = 1$

$x_4 = 1 – 3 = -2$

$x_5 = -2 – 3 = -5$

4. $x_0 = 0$

$x_1 = 2(0) + 1 = 1$

$x_2 = 2(1) + 1 = 3$

$x_3 = 2(3) + 1 = 7$

$x_4 = 2(7) + 1 = 15$

$x_5 = 2(15) + 1 = 31$

5. $x_0 = 5$

$x_1 = 0.5(5) = 2.5$

$x_2 = 0.5(2.5) = 1.25$

$x_3 = 0.5(1.25) = 0.625$

$x_4 = 0.5(0.625) = 0.3125$

$x_5 = 0.5(0.3125) = 0.15625$

b. Iteraciones con crecimiento exponencial o logístico

1. $P_0 = 100$

$P_1 = 2(100) = 200$

$P_2 = 2(200) = 400$

$P_3 = 2(400) = 800$

$P_4 = 2(800) = 1600$

$P_5 = 2(1600) = 3200$

2. $P_0 = 80$

$P_1 = 1.5(80) = 120$

$P_2 = 1.5(120) = 180$

$P_3 = 1.5(180) = 270$

$P_4 = 1.5(270) = 405$

$P_5 = 1.5(405) = 607.5$

3. $P_0 = 50$

$P_1 = 50 + 0.2(50)(1 – \frac{50}{500}) = 50 + 0.2(50)(0.9) = 50 + 9 = 59$

$P_2 = 59 + 0.2(59)(1 – \frac{59}{500}) \approx 59 + 0.2(59)(0.882) \approx 69.4$

$P_3 \approx 69.4 + 0.2(69.4)(1 – \frac{69.4}{500}) \approx 81.1$

$P_4 \approx 81.1 + 0.2(81.1)(0.838) \approx 94.7$

$P_5 \approx 94.7 + 0.2(94.7)(0.811) \approx 110.1$

Problemas

Problema 1. Dinámica de una población en ambiente limitado

Una población de insectos sigue el modelo logístico iterativo:

$P_{n+1} = P_n + 0.1P_n\left(1 – \frac{P_n}{1000}\right)$

Si al inicio hay $P_0 = 100$ insectos, calcula $P_1$ a $P_5$.

Problema 2. Dilución de una sustancia

Una sustancia disminuye su concentración en un 30% con cada paso de purificación. Si la concentración inicial es $C_0 = 120\ \text{mg/L}$, y se aplica la regla: $C_{n+1} = 0.7C_n$. Determina $C_1$ a $C_5$.

Respuestas modelo

Problema 1. Dinámica de una población en ambiente limitado

$P_0 = 100$

$P_1 = 100 + 0.1(100)(1 – \frac{100}{1000}) = 100 + 0.1(100)(0.9) = 100 + 9 = 109$

$P_2 = 109 + 0.1(109)(1 – \frac{109}{1000}) \approx 109 + 9.72 = 118.72$

$P_3 \approx 118.72 + 0.1(118.72)(1 – 0.11872) \approx 129.2$

$P_4 \approx 141.1$

$P_5 \approx 153.8$

Problema 2. Dilución de una sustancia

$C_0 = 120$

$C_1 = 0.7(120) = 84$

$C_2 = 0.7(84) = 58.8$

$C_3 = 0.7(58.8) = 41.16$

$C_4 = 0.7(41.16) = 28.81$

$C_5 = 0.7(28.81) = 20.17$

Recursos digitales

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/rrBCBftz

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/YKpNC2hR

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/rTgKYS4U

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/YXU5hmEZ

• https://ncase.me/polygons-es/

12. Funciones y sus gráficas

Ejercicios

a. Definición de función

1. Si $f(x) = 3x – 2$, calcula: $f(0)$, $f(1)$, $f(4)$

2. Si $f(x) = x^2 + 1$, halla: $f(-1)$, $f(2)$, $f(3)$

3. Dada $f(x) = 5 – 2x$, encuentra: $f(0)$, $f(2)$, $f(5)$

4. Sea $f(x) = \frac{1}{x+1}$. Calcula: $f(0)$, $f(1)$, $f(-1)$

5. Si $f(x) = \sqrt{x + 4}$, determina: $f(0)$, $f(5)$, $f(-3)$

b. Función lineal

1. Grafica $f(x) = 2x + 1$ para $x = -2, -1, 0, 1, 2$

2. Identifica la pendiente y ordenada al origen de $f(x) = -3x + 4$

3. Determina si la recta $f(x) = 0.5x – 2$ es creciente o decreciente

4. Encuentra el punto de corte con el eje Y de $f(x) = -x + 6$

5. Calcula $x$ cuando $f(x) = 0$ en la función $f(x) = 4x – 8$

c. Funciones no lineales

1. Cuadrática: Para $f(x) = x^2 – 6x + 8$, encuentra las raíces

2. Cuadrática: Halla el vértice de $f(x) = -2x^2 + 4x + 1$

3. Exponencial: Evalúa $f(x) = 2 \cdot 3^x$ para $x = 0, 1, 2$

4. Logarítmica: Si $f(x) = 2\log(x)$, encuentra $f(1)$, $f(10)$

5. Racional: Para $f(x) = \frac{1}{x}$, determina $f(1)$, $f(-2)$, $f(0.5)$

d. Dominio y codominio

1. Determina el dominio de $f(x) = \sqrt{x – 2}$

2. Encuentra el dominio de $f(x) = \frac{1}{x^2 – 4}$

3. ¿Cuál es el dominio de $f(x) = \log(x+3)$?

4. Da un ejemplo de una función cuyo dominio sean todos los reales

5. Describe el codominio de $f(x) = x^2$ si $x \in [-3, 2]$

e. Coeficientes de correlación

1. Una correlación de r = 0.95 entre masa y altura sugiere qué tipo de relación?

2. Si r = –0.88 entre tiempo de ejercicio y frecuencia cardiaca, ¿cómo se interpreta?

3. ¿Qué indica r = 0 entre la cantidad de agua y la temperatura?

4. ¿Cuál valor de r indica una correlación lineal perfecta positiva?

5. Explica por qué una correlación alta no implica causalidad

Respuestas modelo

a. Definición de función

1. $f(0) = -2$, $f(1) = 1$, $f(4) = 10$

2. $f(-1) = 2$, $f(2) = 5$, $f(3) = 10$

3. $f(0) = 5$, $f(2) = 1$, $f(5) = -5$

4. $f(0) = 1$, $f(1) = \frac{1}{2}$, $f(-1) = \text{indefinida}$

5. $f(0) = \sqrt{4} = 2$, $f(5) = \sqrt{9} = 3$, $f(-3) = \sqrt{1} = 1$

b. Función lineal

1. Puntos: $(-2, -3)$, $(-1, -1)$, $(0, 1)$, $(1, 3)$, $(2, 5)$

2. Pendiente $m = -3$, ordenada al origen $b = 4$

3. Es decreciente, ya que $m = 0.5 > 0$

4. Punto: $(0, 6)$

5. $4x – 8 = 0 \Rightarrow x = 2$

c. Funciones no lineales

1. $x^2 – 6x + 8 = 0 \Rightarrow (x – 2)(x – 4) = 0 \Rightarrow x = 2,\ 4$

2. Vértice: $x = -\frac{b}{2a} = -\frac{4}{-4} = 1$, $y = f(1) = -2(1)^2 + 4(1) + 1 = 3$, vértice: $(1, 3)$

3. $f(0) = 2$, $f(1) = 6$, $f(2) = 18$

4. $f(1) = 0$, $f(10) \approx 2$

5. $f(1) = 1$, $f(-2) = -0.5$, $f(0.5) = 2$

d. Dominio y codominio

1. $x – 2 \geq 0 \Rightarrow x \geq 2$, dominio: $[2, \infty)$

2. $x^2 – 4 \neq 0 \Rightarrow x \neq \pm2$, dominio: $\mathbb{R} \setminus {-2,\ 2}$

3. $x + 3 > 0 \Rightarrow x > -3$, dominio: $(-3, \infty)$

4. Ejemplo: $f(x) = x^3$, dominio: $\mathbb{R}$

5. $x^2 \in [0, 9]$ para $x \in [-3, 2]$, codominio: $[0, 9]$

e. Coeficientes de correlación

1. Fuerte correlación positiva: al aumentar la masa, también aumenta la altura

2. Fuerte correlación negativa: a más ejercicio, menor frecuencia cardiaca

3. No hay relación lineal entre agua y temperatura

4. r = 1

5. Porque pueden estar influenciadas por una tercera variable o por coincidencia estadística

Problemas

Problema 1. Crecimiento de células inmunes

Durante una respuesta inmune, una población de células T se duplica cada 12 horas.

a. Si se parte de 1000 células, ¿cuántas habrá en 24 horas?

b. ¿Cuántas habrá después de 36 horas?

c. ¿Después de cuántas horas se superarán las 32,000 células?

Usa: $f(t) = 1000 \cdot 2^{t/12}$, donde $t$ está en horas.

Problema 2. Efecto de dosis de fármaco en respuesta fisiológica

Una investigadora estudia el efecto de un fármaco, midiendo la respuesta como: $R(x) = 10 \cdot \log(x + 1)$

a. ¿Cuál es la respuesta cuando la dosis es de 1 mg?

b. ¿Y cuando es de 9 mg?

c. ¿Qué ocurre si se duplica la dosis de 4 mg a 8 mg?

Respuestas modelo

Problema 1. Células inmunes

a. $f(24) = 1000 \cdot 2^{2} = 1000 \cdot 4 = 4000$

b. $f(36) = 1000 \cdot 2^{3} = 1000 \cdot 8 = 8000$

c. Buscamos $t$ tal que $1000 \cdot 2^{t/12} > 32000$

Dividiendo: $2^{t/12} > 32$

Como $2^5 = 32$, entonces $\frac{t}{12} > 5 \Rightarrow t > 60$

Respuesta: después de 60 horas

Problema 2. Dosis y respuesta

a. $R(1) = 10 \cdot \log(2) \approx 10 \cdot 0.301 = 3.01$

b. $R(9) = 10 \cdot \log(10) = 10 \cdot 1 = 10$

c. $R(4) = 10 \cdot \log(5) \approx 10 \cdot 0.699 = 6.99$,

$R(8) = 10 \cdot \log(9) \approx 10 \cdot 0.954 = 9.54$

La respuesta no se duplica, el crecimiento es más lento por la naturaleza logarítmica

13. Sistemas de ecuaciones lineales

Ejercicios

a. Tipos de soluciones

Para cada sistema, indica el tipo de solución (única, infinitas o ninguna).

1. $\begin{cases} x + y = 4 \ x – y = 2 \end{cases}$

2. $\begin{cases} 2x – y = 4 \ 4x – 2y = 8 \end{cases}$

3. $\begin{cases} 3x + y = 7 \ 3x + y = 2 \end{cases}$

4. $\begin{cases} y = 2x + 1 \ y = -x + 4 \end{cases}$

5. $\begin{cases} 2x + 3y = 6 \ 4x + 6y = 12 \end{cases}$

b. Método gráfico

Grafica cada sistema y determina visualmente su solución.

1. $\begin{cases} y = x + 1 \ y = -x + 5 \end{cases}$

2. $\begin{cases} y = 2x – 3 \ y = 2x + 1 \end{cases}$

3. $\begin{cases} x + y = 3 \ x – y = 1 \end{cases}$

4. $\begin{cases} y = -x + 2 \ y = x – 4 \end{cases}$

5. $\begin{cases} y = 0.5x \ y = -2x + 5 \end{cases}$

c. Método de sustitución

Resuelve cada sistema usando sustitución.

1. $\begin{cases} x + y = 7 \ x – y = 1 \end{cases}$

2. $\begin{cases} x = 2y \ x + y = 6 \end{cases}$

3. $\begin{cases} y = 3x – 5 \ 2x + y = 7 \end{cases}$

4. $\begin{cases} x = y + 4 \ x + y = 10 \end{cases}$

5. $\begin{cases} y = -x + 2 \ 2x + y = 4 \end{cases}$

d. Método de igualación

Resuelve cada sistema usando igualación.

1. $\begin{cases} y = 2x + 1 \ y = -x + 4 \end{cases}$

2. $\begin{cases} y = x – 3 \ y = -2x + 6 \end{cases}$

3. $\begin{cases} y = 3x + 2 \ y = x + 6 \end{cases}$

4. $\begin{cases} y = \frac{1}{2}x + 4 \ y = -x + 1 \end{cases}$

5. $\begin{cases} y = 4x – 5 \ y = 2x + 1 \end{cases}$

e. Método de reducción

Resuelve cada sistema usando reducción (suma o resta).

1. $\begin{cases} x + y = 8 \ x – y = 2 \end{cases}$

2. $\begin{cases} 3x + 2y = 12 \ 5x – 2y = 8 \end{cases}$

3. $\begin{cases} 4x + y = 11 \ -4x + 2y = -6 \end{cases}$

4. $\begin{cases} 2x + 3y = 7 \ 4x + 6y = 14 \end{cases}$

5. $\begin{cases} x – 2y = 1 \ 2x + y = 7 \end{cases}$

Respuestas modelo

a. Tipos de soluciones

1. Una única solución

2. Infinitas soluciones

3. Ninguna solución

4. Una única solución

5. Infinitas soluciones

b. Método gráfico (estimación visual)

1. Se cortan en (2, 3)

2. Son paralelas → ninguna solución

3. Se cortan en (2, 1)

4. Se cortan en (3, -1)

5. Se cortan en (2, 1)

c. Método de sustitución

1. $x = 4$, $y = 3$ → (4, 3)

2. $x = 4$, $y = 2$ → (4, 2)

3. Sustituimos: $2x + (3x – 5) = 7 \Rightarrow 5x = 12 \Rightarrow x = \frac{12}{5}$

$y = 3 \cdot \frac{12}{5} – 5 = \frac{36}{5} – 5 = \frac{11}{5}$ → $\left( \frac{12}{5}, \frac{11}{5} \right)$

4. $x = y + 4$, sustituyendo: $y + 4 + y = 10 \Rightarrow 2y = 6 \Rightarrow y = 3$, $x = 7$ → (7, 3)

5. $y = -x + 2$, sustituyendo en la otra: $2x + (-x + 2) = 4 \Rightarrow x = 2$, $y = 0$ → (2, 0)

d. Método de igualación

1. $2x + 1 = -x + 4 \Rightarrow 3x = 3 \Rightarrow x = 1$, $y = 3$ → (1, 3)

2. $x – 3 = -2x + 6 \Rightarrow 3x = 9 \Rightarrow x = 3$, $y = 0$ → (3, 0)

3. $3x + 2 = x + 6 \Rightarrow 2x = 4 \Rightarrow x = 2$, $y = 8$ → (2, 8)

4. $\frac{1}{2}x + 4 = -x + 1 \Rightarrow \frac{3}{2}x = -3 \Rightarrow x = -2$, $y = 3$ → (-2, 3)

5. $4x – 5 = 2x + 1 \Rightarrow 2x = 6 \Rightarrow x = 3$, $y = 7$ → (3, 7)

e. Método de reducción

1. Sumamos: $2x = 10 \Rightarrow x = 5$, $y = 3$ → (5, 3)

2. Sumamos: $8x = 20 \Rightarrow x = 2.5$, $y = 2.25$ → (2.5, 2.25)

3. Sumamos: $3y = 5 \Rightarrow y = \frac{5}{3}$, $x = \frac{11 – \frac{5}{3}}{4} = \frac{28}{12} = \frac{7}{3}$ → $\left( \frac{7}{3}, \frac{5}{3} \right)$

4. Reducción directa: las ecuaciones son múltiplos → infinitas soluciones

5. Multiplicamos primera por 2: $2x – 4y = 2$

Restamos: $2x – 4y – (2x + y) = 2 – 7 \Rightarrow -5y = -5 \Rightarrow y = 1$

$x = 1 + 2 = 3$ → (3, 1)

Problemas

Problema 1. Mezcla de soluciones

En un laboratorio necesita preparar 10 litros de una solución al 40% de sal. Se tiene disponibles soluciones al 30% y al 60%.

Sea x la cantidad (en litros) de solución al 30% e y la del 60%.

a. ¿Cuántos litros de cada solución debe mezclar?

Problema 2. Nutrición celular

Una célula requiere exactamente 12 mg de proteína y 18 mg de glucosa. Dos soluciones nutritivas ofrecen:

• Solución A: 2 mg de proteína y 3 mg de glucosa por gota

• Solución B: 4 mg de proteína y 3 mg de glucosa por gota

¿Cuántas gotas de cada solución se necesitan para satisfacer los requerimientos?

Respuestas modelo

Problema 1. Mezcla de soluciones

Sistema:

$\begin{cases} x + y = 10 \ 0.30x + 0.60y = 0.40 \cdot 10 = 4 \end{cases}$

Multiplicamos segunda por 100:

$30x + 60y = 400$

Reducimos usando la primera:

$x = 10 – y$

$30(10 – y) + 60y = 400 \Rightarrow 300 – 30y + 60y = 400 \Rightarrow 30y = 100 \Rightarrow y = \frac{10}{3}$

$x = \frac{20}{3}$

Solución: Mezclar $\frac{20}{3} \approx 6.67$ L de solución al 30% y $\frac{10}{3} \approx 3.33$ L de la del 60%.

Problema 2. Nutrición celular

Sistema:

$\begin{cases} 2x + 4y = 12 \ 3x + 3y = 18 \end{cases}$

Simplificamos segunda: $x + y = 6$

Primera: $2x + 4y = 12$

Multiplicamos segunda por 2: $2x + 2y = 12$

Restamos: $2x + 4y – (2x + 2y) = 12 – 12 \Rightarrow 2y = 0 \Rightarrow y = 0$

$x = 6$

Solución: 6 gotas de solución A y 0 gotas de B.

14. Matrices y determinantes

Ejercicios

a. Definición de matriz

1. Identifica $$a_{12}$ en la matriz $A = \begin{bmatrix} 7 & 8 & 9 \ 4 & 5 & 6 \end{bmatrix}$$

2. Determina el tamaño de la matriz $$B = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 \ 5 & 6 \ 8 & 9 \end{bmatrix}$$

3. ¿Cuánto vale $a_{31}$ en la matriz? $$C = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \ 3 & 4 \ 5 & 6 \end{bmatrix}$$

4. Da el valor de $a_{22}$ en la matriz $$D = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \ 3 & 4 & 5 \end{bmatrix}$$

5. ¿Qué posición ocupa el número 4 en la matriz? $$E = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 4 \ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$$

b. Tipos de matrices

Clasifica la matriz

1. $F = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 \ 4 & 5 & 6 \end{bmatrix}$

2. $G = \begin{bmatrix} 7 \ 8 \ 9 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $H = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$

4. $I = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}$

5. $J = \begin{bmatrix} 6 & 0 \ 0 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$

c. Operaciones con matrices

Resuelve

• Suma y resta de matrices

1. $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \ 3 & 4 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 4 & 3 \ 2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$

2. $\begin{bmatrix} 5 & 6 \ 7 & 8 \end{bmatrix} – \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \ 3 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $\begin{bmatrix} 9 & 0 \ -2 & 3 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} -4 & 5 \ 6 & -1 \end{bmatrix}$

• Multiplicación por un escalar

1. $3 \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -2 \ 0 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$

2. $-2 \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 5 \ -1 & 2 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $\frac{1}{2} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 6 & 8 \ 4 & 2 \end{bmatrix}$

• Multiplicación de matrices

1. $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 3 \ 4 \end{bmatrix}$

2. $\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 0 \ 1 & 3 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 4 \ 2 & 5 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 2 \ 0 \ 3 \end{bmatrix}$

d. Determinantes

1. Calcula el determinante de $$A = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 \ 1 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$$

2. Calcula el determinante de $$B = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 5 \ -2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$$

3. Usa la regl de Sarrus para $$C = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 2 \ -1 & 3 & 1 \ 2 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$$

4. ¿Cuál es el determinante de D? $$D = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & -3 \ 4 & 5 \end{bmatrix}$$

5. Usa la regla de Sarrus en E. $$E = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 1 & 3 \ 0 & -1 & 2 \ 4 & 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}$$

e. Matriz inversa

1. Verifica si la matriz $A = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 5 \ 1 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$ tiene inversa

2. Calcula la inversa de $A = \begin{bmatrix} 4 & 7 \ 2 & 6 \end{bmatrix}$

3. Verifica si $B = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \ 2 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$ es invertible

4. Encuentra $A^{-1}$ si $A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$

5. Verifica que $A \cdot A^{-1} = I$ para $A = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 1 \ 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$

f. Resolución de sistemas con matrices

Resuelve

1. $\begin{cases} x + y = 6 \ 2x – y = 3 \end{cases}$

2. $\begin{cases} 3x + 2y = 7 \ x – y = 1 \end{cases}$

3. $\begin{cases} x + 2y = 5 \ 4x + y = 6 \end{cases}$

4. $\begin{cases} 2x + 3y = 8 \ x – 2y = -3 \end{cases}$

5. $\begin{cases} x + y = 4 \ x – y = 2 \end{cases}$

Respuestas modelo

a. Definición de matriz

1. $a_{12} = 8$

2. Matriz $3 \times 2$

3. $a_{31} = 5$

4. $a_{22} = 4$

5. Está en la posición $(1,2)$

b. Tipos de matrices

1. Rectangular

2. Columna

3. Identidad (cuadrada)

4. Nula

5. Diagonal (cuadrada)

c. Operaciones con matrices

• Suma y resta de matrices

1. $\begin{bmatrix} 5 & 5 \ 5 & 5 \end{bmatrix}$

2. $\begin{bmatrix} 4 & 4 \ 4 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $\begin{bmatrix} 5 & 5 \ 4 & 2 \end{bmatrix}$

• Multiplicación por un escalar

1. $\begin{bmatrix} 3 & -6 \ 0 & 12 \end{bmatrix}$

2. $\begin{bmatrix} -6 & -10 \ 2 & -4 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 4 \ 2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$

• Multiplicación de matrices

1. $1 \cdot 3 + 2 \cdot 4 = 3 + 8 = \boxed{11}$

2. $\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 8 \ 7 & 19 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $1 \cdot 2 + (-1) \cdot 0 + 2 \cdot 3 = 2 + 0 + 6 = \boxed{8}$

d. Determinantes

1. $\det = 2 \cdot 4 – 3 \cdot 1 = 8 – 3 = 5$

2. $\det = 0 \cdot 3 – 5 \cdot (-2) = 10$

3. $\det = (1)(3)(1) + (0)(1)(2) + (2)(-1)(1) – (2)(3)(2) – (1)(1)(1) – (0)(-1)(1) = 3 + 0 – 2 – 12 – 1 – 0 = -12$

4. $\det = 2 \cdot 5 – (-3) \cdot 4 = 10 + 12 = 22$

5. $\det = 2(-1)(0) + 1(2)(4) + 3(0)(1) – 3(-1)(4) – 2(2)(1) – 1(0)(0) = 0 + 8 + 0 – (-12) – 4 – 0 = 16$

e. Matriz inversa

1. $\det = 2 \cdot 3 – 1 \cdot 5 = 6 – 5 = 1 \Rightarrow$ sí tiene inversa

2. $\det = 4 \cdot 6 – 7 \cdot 2 = 24 – 14 = 10$

$A^{-1} = \frac{1}{10} \begin{bmatrix} 6 & -7 \ -2 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$

3. $\det = 1 \cdot 4 – 2 \cdot 2 = 0 \Rightarrow$ no es invertible

4. $\det = 1 \cdot 3 – (-1) \cdot 2 = 3 + 2 = 5$

$A^{-1} = \frac{1}{5} \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 1 \ -2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$

5. $A^{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \ -1 & 2 \end{bmatrix}$

$A \cdot A^{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 1 \ 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \ -1 & 2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} = I$

f. Resolución de sistemas con matrices

1. $A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \ 2 & -1 \end{bmatrix},\ B = \begin{bmatrix} 6 \ 3 \end{bmatrix},\ \det = -3$

$A^{-1} = \frac{1}{-3} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & -1 \ -2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$

$X = A^{-1}B = \begin{bmatrix} 3 \ 3 \end{bmatrix}$

2. $x = 3,\ y = 2$

3. $x = 1,\ y = 2$

4. $x = 0,\ y = \frac{8}{3}$

5. $x = 3,\ y = 1$

Problemas

Problema 1. Transporte de proteínas

Si se modela el flujo de proteínas entre dos compartimientos celulares con la matriz de transferencia:

$A = \begin{bmatrix} 0.7 & 0.3 \ 0.4 & 0.6 \end{bmatrix}$

y la distribución inicial es $B = \begin{bmatrix} 100 \ 50 \end{bmatrix}$.

a. ¿Cuál es la distribución luego de un ciclo?

b. ¿Y luego de dos ciclos?

Problema 2. Ecuaciones químicas

Un sistema de ecuaciones químicas está dado por:

$\begin{cases} 2x + 3y = 16 \ 4x – y = 10 \end{cases}$

a. Escribe el sistema como $AX = B$

b. Encuentra $X$ usando matrices

c. Interpreta el resultado si $x$ y $y$ representan cantidades de reactivos

Respuestas modelo

Problema 1. Transporte de proteínas

a. $AB = \begin{bmatrix} 0.7 & 0.3 \ 0.4 & 0.6 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 100 \ 50 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 85 \ 70 \end{bmatrix}$

b. Repetimos:

$A \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 85 \ 70 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.7(85) + 0.3(70) \ 0.4(85) + 0.6(70) \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 79.5 + 21 = 100.5 \ 34 + 42 = 76 \end{bmatrix}$

Problema 2. Ecuaciones químicas

a. $A = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 \ 4 & -1 \end{bmatrix},\ X = \begin{bmatrix} x \ y \end{bmatrix},\ B = \begin{bmatrix} 16 \ 10 \end{bmatrix}$

b. $\det = 2(-1) – 3(4) = -2 – 12 = -14$

$A^{-1} = \frac{1}{-14} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & -3 \ -4 & 2 \end{bmatrix}$

$X = A^{-1}B = \begin{bmatrix} 2 \ 4 \end{bmatrix}$

c. Se necesitan 2 unidades del primer reactivo y 4 del segundo para cumplir la reacción.

Recursos digitales

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/KNRxr9bn

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/un4g8hkx

• https://www.geogebra.org/m/xtr5qmcb