En coordenadas rectangulares la longitud de arco de una curva parametrizada la calculamos con la integral $$\int\limits_{t_0}^{t_1} \Big\|{\alpha}’ (t) \Big\| dt$$

Si $\alpha (t) = \big( x (t), y (t) \big)$, y ${\alpha}’ (t) = \big( x’ (t) , y’ (t) \big)$, entonces $$\int\limits_{t_0}^{t_1} \sqrt{ \big( x’ (t)\big)^2 + \big(y’ (t) \big)^2 \, } dt $$

¿Qué integral habría que calcular si la curva está en otras coordenadas?

Por ejemplo: en coordenadas polares, es decir, si conocemos $ r (t)$ y $\theta (t)$

Entonces

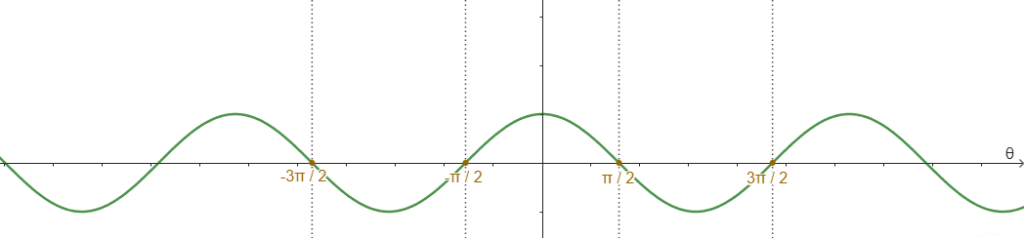

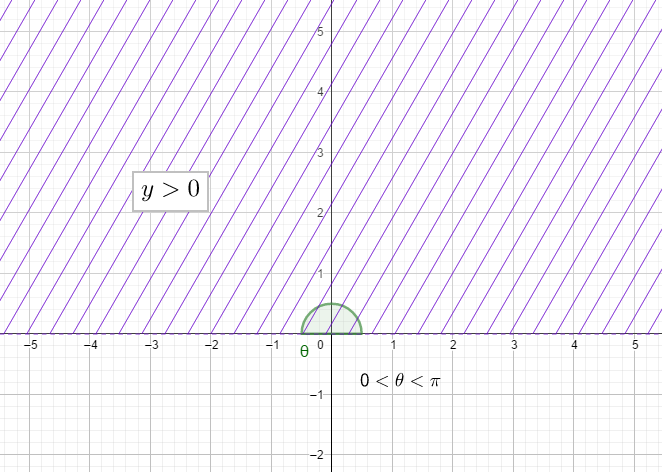

$ x (t) = r (t) \cos \big( \theta (t) \big)$

$ y (t) = r (t) \sin \big( \theta (t) \big)$

Derivando

$ x’ (t) = r’ (t) \cos \big( \theta (t) \big) \, – \, r (t) {\theta}’ (t) \sin \big( \theta (t) \big)$

$ y’ (t) = r’ (t) \sin \big( \theta (t) \big) \, + \, r (t) {\theta}’ (t) \cos \big( \theta (t) \big)$

Luego

$\begin{align*} \big( x’ (t)\big)^2 + \big(y’ (t) \big)^2 &= \Big( r’ (t) \cos \big( \theta (t) \big) \, – \, r (t) {\theta}’ (t) \sin \big( \theta (t) \big) \Big)^2 + \Big( r’ (t) \sin \big( \theta (t) \big) \, + \, r (t) {\theta}’ (t) \cos \big( \theta (t) \big) \Big)^2 \\ &= \textcolor{Green}{ {r’}^2 {\cos}^2 \theta (t)} \, – \, \cancel{ \textcolor{Red}{2 r’ (t) r (t) {\theta}’ (t) \cos \theta (t) \sin \theta (t)}} + \textcolor{DarkBlue}{r^2 (t) {{\theta}’}^2 (t) {\sin}^2 \theta (t) } \\ & + \textcolor{Green}{ {r’}^2 {\cos}^2 \theta (t)} + \cancel{ \textcolor{Red}{2 r’ (t) r (t) {\theta}’ (t) \cos \theta (t) \sin \theta (t)}} + \textcolor{DarkBlue}{r^2 (t) {{\theta}’}^2 (t) {\sin}^2 \theta (t)} \\ &= \Big( r’ (t) \Big)^2 + r^2 (t) \Big( {\theta}’ (t) \Big)^2 \end{align*} $

Entonces $$\int\limits_{t_0}^{t_1} \sqrt{ \Big( r’ (t) \Big)^2 + r^2 (t) \Big( {\theta}’ (t) \Big)^2 \, } dt$$

${}$

La «notación diferencial»

$$ ds^2 = dx^2 + dy^2 \; \; \longrightarrow \; \; \Big(\dfrac{ds}{dt}\Big)^2 = \Big(\dfrac{dx}{dt}\Big)^2 + \Big(\dfrac{dy}{dt}\Big)^2$$

Entonces $$\int ds = \int \dfrac{ds}{dt} dt$$

En coordenadas polares

$ds^2 = dr^2 + r^2 d{\theta}^2 \longleftrightarrow \Big(\dfrac{ds}{dt}\Big)^2 = \Big(\dfrac{dr}{dt}\Big)^2 + r^2 \Big(\dfrac{d \theta}{dt}\Big)^2$

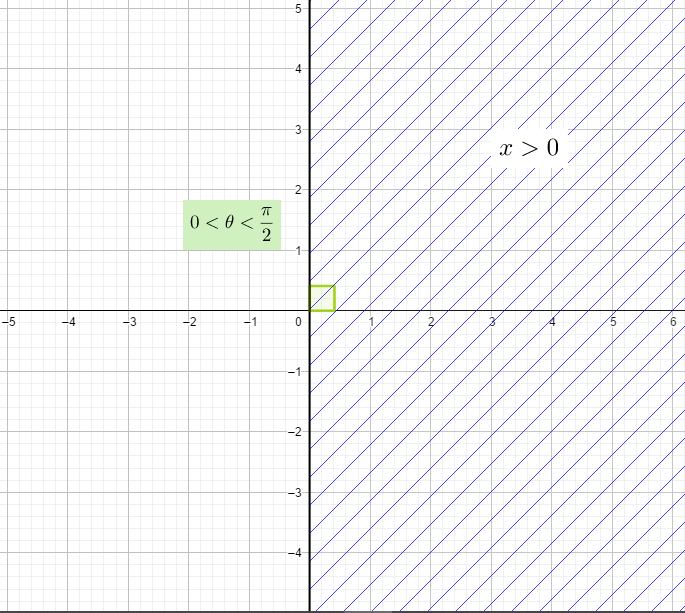

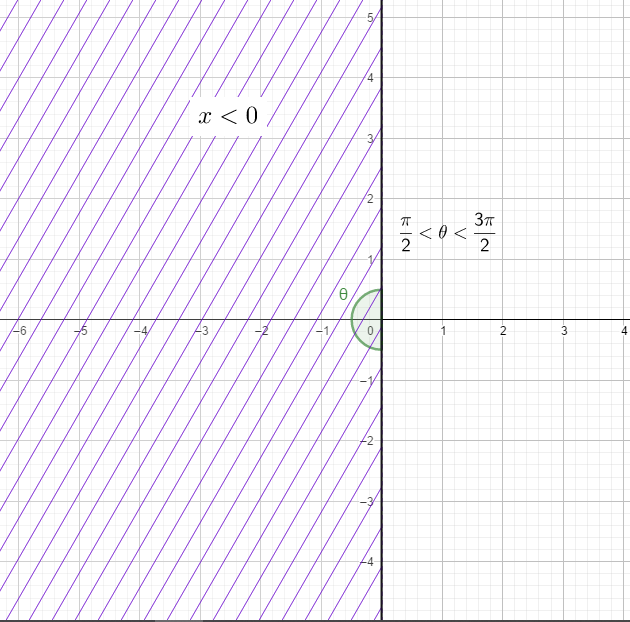

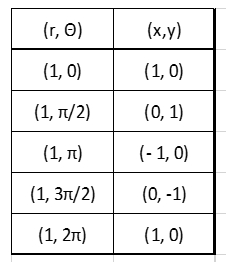

Queremos que $ T \, o \, \beta = \alpha$

$T ( r, \theta) = (x, y)$

$x = r \cos \theta$

$y = r \sin \theta$

$x (t) = r (t) \cos \theta (t)$

$y (t) = r (t) \sin \theta (t)$

La «diferencial de T» ( o derivada de $T$)

$$DT = \begin{equation*} \left( \begin{matrix} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial r} & \; \; & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial \theta}\\ {} \\ \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial r} & \; \; & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial \theta}\end{matrix} \right) \end{equation*}$$

Esta matriz es la transformación lineal que asocia vectores tangentes en el plano $r \theta$ con vectores tangentes en el plano $xy.$

Luego $DT \cdot {\beta}’ = {\alpha}’$

Entonces $ \begin{equation*} \left( \begin{matrix} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial r} = \cos \theta & \; \; & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial \theta} = – \, r \sin \theta \\ {} \\\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial r} = \sin \theta & \; \; & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial \theta} = r \cos \theta \end{matrix} \right) \end{equation*}$

Entonces $$ \begin{equation*} \left( \begin{matrix} \cos \theta & \; \; & – \, r \sin \theta \\ {} \\ \sin \theta & \; \; & r \cos \theta \end{matrix} \right) \left( \begin{matrix} r’ \\ {} \\ {\theta}’ \end{matrix} \right) = \left( \begin{matrix} x’ \\ {} \\ y’ \end{matrix} \right) \end{equation*}$$

Luego

$ x’ = r’ \cos \theta \, – \, r {\theta}’ \sin \theta$

$ y’ = r’ \sin \theta \, + \, r {\theta}’ \cos \theta$

Para pedir la $\|{\alpha}’t\|$ usamos el producto punto

${\alpha}’ \cdot {\alpha}’=\|{\alpha}’\|^2$

$\sqrt{{\alpha}’ \cdot {\alpha}’}=\|{\alpha}’\|$

Si tenemos $T:V \longrightarrow W$ transf. lineal, y tenemos una función bilineal

$b:W \times W \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}$

podemos formar otra función bilineal B, tal que $B:V\times V \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

$B( v_1 , v_2) := b(Tv_1, Tv_2)$

Vamos a medir el tamaño de los vectores en el plano $(r, \theta)$ no con la norma del producto punto sino con la norma de este producto escalar

$\begin{align*}B \Big( ({r’}_1, {\theta}’_1) , ({r’}_2, {\theta}’_2) \Big) &= b \Big( DT ({r’}_1, {\theta}’_1) , DT ({r’}_2, {\theta}’_2) \Big) \\ &= DT \begin{pmatrix} {r’}_1 \\ {\theta}’_1 \end{pmatrix} \cdot DT \begin{pmatrix} {r’}_2\\ {\theta}’_2 \end{pmatrix}\end{align*}$

$\begin{align*} \Big( {r’}_1 \cos \theta \, – \, r {\theta}’_1 \sin \theta , {r’}_1 \sin \theta \, + \, r {\theta}’_1 \cos \theta \Big) \cdot \Big( {r’}_2 \cos \theta \, – \, r {\theta}’_2 \sin \theta , {r}’_2 \sin \theta \, + \, r {\theta}’_2 \cos \theta \Big) \\ = \textcolor{Orange}{ {r}’_1 {r}’_2 {\cos}^2 \theta } \, – \, \cancel{ \textcolor{Red}{ {r’}_1 r {\theta}’_2 \cos \theta \sin \theta }} \, – \, \textcolor{DarkBlue}{{r}’_2 {\theta}’_1 \sin \theta \cos \theta } \\ + \textcolor{Green}{ {r}^2 {\theta}’_1 {\theta}’_2 {\sin}^2 \theta } + \textcolor{Orange}{ {r}’_1 {r}’_2 {\cos}^2 \theta } \, – \, \cancel{ \textcolor{Red}{ {r’}_1 r {\theta}’_2 \cos \theta \sin \theta }} \\ \, – \, \textcolor{DarkBlue}{{r}’_2 {\theta}’_1 \sin \theta \cos \theta } + \textcolor{Green}{ {r}^2 {\theta}’_1 {\theta}’_2 {\sin}^2 \theta } \\ = {r}’_1 {r}’_2 \, + \, {r’} {\theta}’_1 {\theta}’_2 \end{align*} $

Nueva norma para los vectores tangentes $\big( r’, {\theta}’ \big)$ en el plano $ ( r, \theta)$ $$\big\| \big( r’, {\theta}’ \big) \big\| : = \sqrt{{r’}^2 + r^2 {{\theta}’}^2 \, }$$

${}$

Jacobiano $= \begin{vmatrix} \cos \theta & \; \; \; & \; \; \sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \; \; \; & \,- \ \cos \theta\end{vmatrix} = r \cos^2 \theta + r \sin^2 \theta = r $

En general, si tenemos un cambio de coordenadas

$ x = f (u, v)$

$ y = g (u, v)$

Sus derivadas son

$\dfrac{dx}{dt} = \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial u} \dfrac{du}{dt} + \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial v} \dfrac{dv}{dt}$

$\dfrac{dy}{dt} = \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial u} \dfrac{du}{dt} + \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial v} \dfrac{dv}{dt}$

Entonces

$\begin{pmatrix} \dfrac{dx}{dt} \\ {} \\ \dfrac{dy}{dt} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \; \; & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial v} \\{}\\ \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \; \; & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial v} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \dfrac{du}{dt} \\ {} \\ \dfrac{dv}{dt} \end{pmatrix}$

Luego

$\begin{align*} \int\limits_{t_0}^{t_1} \big\|{\alpha}’ (t) \big\| dt &= \int\limits_{t_0}^{t_1} \sqrt{ \Big( \dfrac{dx}{dt}\Big)^2 \, + \, \Big( \dfrac{dy}{dt}\Big)^2 \, } dt \\ &= \int\limits_{t_0}^{t_1} H \Big( \dfrac{du}{dt} \, , \, \dfrac{dv}{dt} \Big) dt \end{align*} $

${}$

Longitud de arco de una curva en $\mathbb{R}^3$,

(*) en coordenadas cartesianas $$\textcolor{Red}{ds^2 = dx^2 \, + \, dy^2 \, + \, dz^2} $$

(*) en coordenadas cilíndricas $$\textcolor{Green}{ds^2 = dr^2 \, + \, r d{\theta}^2 \, + \, dz^2} $$

(*) en coordenadas esféricas $$\textcolor{DarkBlue}{ds^2 = dr^2 \, + \, r^2 \Big( d{\theta}^2 \, + \, {\sin}^2 \theta \; d{\varphi}^2 \Big) }$$