Teorema de la función implícita:

Sea $F : \mathcal{U} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ con derivadas parciales continuas $F_x$, $F_y$ en una vecindad de un punto $(x_0, y_0)$ tal que $F (x_0, y_0) = 0$ y además $F_y (x_0, y_0) \neq 0$, entonces existe un rectángulo $\big[ x_0 \, – \, \alpha , x_0 \, + \, \alpha \big] \times \big[ y_0 \, – \, \beta , y_0 \, + \, \beta \big]$ tal que para cada $x$ en el intervalo $\big[ x_0 \, – \, \alpha , x_0 \, + \, \alpha \big]$ la ecuación $F ( x, y) = 0$ tiene una solución $ y = f (x)$ con $ y_0 \, – \, \beta \leq y \leq y_0 \, + \, \beta. $

Dicha función $ f : \big[ x_0 \, – \, \alpha , x_0 \, + \, \alpha \big] \rightarrow \big[ y_0 \, – \, \beta , y_0 \, + \, \beta \big]$ satisface la condición $f (x_0) = y_0$ y para toda $ x \in \big[ x_0 \, – \, \alpha , x_0 \, + \, \alpha \big] $ cumple que

$F ( x, f (x) ) = 0$

$F_y ( x, f (x) ) \neq 0$

Más aún, $f$ es continua con derivada continua, y está dada por la ecuación

$$ f’ (x) = \, – \, \dfrac{F_x ( x, f (x) )}{F_y ( x, f (x) )}$$

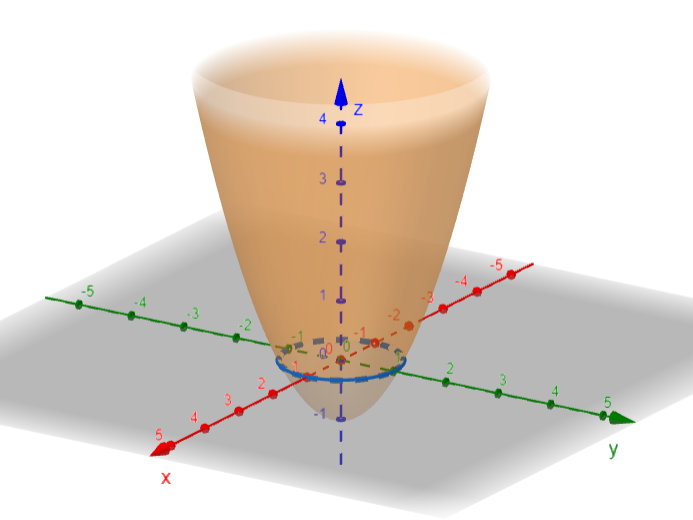

EJEMPLO: La circunferencia unitaria

Sea $F : \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

$ F : (x, y) = x^2 + y^2 \, – \, 1$

Curva de nivel cero.

$\big\{ (x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \Big| x^2 + y^2 \, – \, 1 = 0 \big\}$

Vamos a calcular las derivadas parciales:

$F_x (x, y) = 2x $

$F_y (x, y) = 2y $

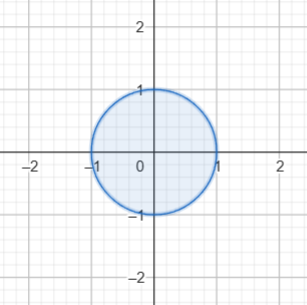

Tomemos un punto $(x_0 , y_0)$ tal que $ F (x_0 , y_0) = 0$ y $ F_y (x_0 , y_0) \neq 0$.

Por simplicidad elegimos $(x_0 , y_0) = (0, 1)$ y podemos tomar $\mathcal{R} = \big[ – \dfrac{1}{2} , \dfrac{1}{2} \big] \times \big[ \dfrac{1}{2} , \dfrac{3}{2} \big]$

$x^2 + y^2 \, – \, 1 = 0 \, \iff \, y^2 = 1 \, – \, x^2 \, \iff \, y = \pm \sqrt{1 \, – \, x^2 \, }$

Por lo tanto $ \textcolor{DarkGreen}{ f (x) = \sqrt{1 \, – \, x^2 \, }}$

Comprobemos que $F (x, f (x)) = 0$ en $(-1, 1)$

$F (x, f (x)) = x^2 + ( f (x) )^2 \, – \, 1 $

$F (x, f (x)) = x^2 + \Big( \sqrt{1 \, – \, x^2 \, } \Big)^2 \, – \, 1 $

$F (x, f (x)) = \textcolor{Red}{ \cancel{x^2}} + \textcolor{Blue}{\cancel{1}} \, – \, \textcolor{Red}{\cancel{x^2}} \, \, – \, \textcolor{Blue}{\cancel{1}}$

$F (x, f (x)) = 0 \; \; \; \forall \; (x, f (x)) \in \mathcal{I} $

Observación:

¿Qué sucede si ignoramos la hipótesis y consideramos, por ejemplo, $(x_0, y_0) = (1,0)$?

Sucedería que ninguna vecindad del punto queda descrita como la gráfica de una función.

Si $f (x) $ es una función diferenciable tal que $F (x, f (x) ) \equiv 0$, entonces $ h (x) = F (x, f (x) )$ es diferenciable y $h’ (x) \equiv 0.$

$ h (x) = ( F \, o \, \alpha) (x) $ , con $\alpha (x) = (x, f (x) )$

Entonces

$ \begin{align*} h’ (x) &= ( F \, o \, \alpha)’ (x) \\ &= \nabla F ( \alpha (x) ) \cdot {\alpha}’ (x) \end{align*}$ . . . (1)

Tenemos que

$ \alpha’ (x) = ( 1, f’ (x) )$ . . . (2)

$\nabla F ( x, y) = \Big( \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial x} (x, y), \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial y} (x, y) \Big)$ . . . (3)

Luego, sustituyendo (2) y (3) en (1) tenemos que

$\begin{align*} \nabla F ( \alpha (x) ) \cdot {\alpha}’ (x) &= \nabla F ( x, f (x) ) \cdot (1, f’ (x) ) \\ &= \Big( \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial x} (x, f (x)), \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial y} (x, f (x)) \Big) \cdot (1, f’ (x) ) \\ &= \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial x} (x, f (x)) \, + \, f’ (x) \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial y} (x, f (x)) = 0 \end{align*}$

Despejando $f’ (x)$ de la última igualdad, tenemos que

$$\textcolor{Purple}{f’ (x) = \dfrac{- \, \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial x} (x, f (x)) }{\dfrac{\partial F}{\partial y} (x, f (x)) }}$$

EJEMPLO

$f (x) = \sqrt{ 1 \, – \, x^2 \, } = ( 1 \, – \, x^2 )^{1/2} $

Entonces

$f’ (x) = \dfrac{1}{\cancel{2}} ( 1 \, – \, x^2 )^{-1/2} (-\, \cancel{2}x) = \dfrac{- \, x}{\sqrt{ 1 \, – \, x^2 \, }}$

$F_x (x, y) = 2x$ $F_y (x, y) = 2y$

$ \dfrac{- \, \dfrac{\partial F}{\partial x} (x, f (x)) }{\dfrac{\partial F}{\partial y} (x, f (x)) } = \dfrac{ – \, 2x}{2y} = \dfrac{- \, x}{f (x)} = \dfrac{ – \, x}{\sqrt{ 1 \, – \, x^2 \, }} = f’ (x)$

Observaciones:

(*) Podríamos aproximar $f (x)$ con su polinomio de Taylor $ f (x_0) + f’ (x_0) ( x \, – \, x_0)$ ya que

$f (x_0) = y_0$ que lo conocemos.

Y además también conocemos $ f’ (x) = \dfrac{- \, F_x (x_0, y_0) }{F_y (x_0, y_0) }$

(*) Podríamos calcular ${f’}’ (x) $ como sigue:

$\begin{align*} {f’}’ (x) &= \dfrac{d}{dx} \Bigg( \dfrac{- \, F_x (x, f (x)) }{ F_y (x, f (x)) } \Bigg) \\ &= \dfrac{d}{dx} \Bigg( \dfrac{- \, F_x (x, f (x)) }{ F_y (x, f (x)) } \Bigg) \\ &= \, – \; \dfrac{ F_y (x, f (x)) \dfrac{d}{dx} F_x (x, f (x)) \, – \, F_x (x, f (x)) \dfrac{d}{dx} F_y (x, f (x))}{\Big( F_y (x, f (x)) \Big)2} \\ &= \, – \; \dfrac{ F_y (x, f (x)) \Big( F_{xx} (x, f (x)).1 \, + \, F_{xy} (x, f (x)) (f’ (x)) \Big) \, – \, F_x (x, f (x)) \Big( F_{xy} (x, f (x)).1 \, + \, F_{yy} (x, f (x)) (f’ (x)) \Big) }{\Big( F_y (x, f (x)) \Big)^2} \end{align*}$

Entonces

$ {f’}’ (x) = \, – \; \dfrac{ F_y F_{xx} \, + \, F_{xy} \Big(- \, \dfrac{F_x}{\cancel{F_y}} \cancel{F_y} \Big) \, – \, F_x F_{xy} \, + \, F_x F_{yy} \Big(- \, \dfrac{F_x}{F_y} \Big) }{\Big( F_y \Big)^2}$

multiplicando por $\dfrac{F_y}{F_y}$

$ {f’}’ (x) = \, – \; \dfrac{ F^2_y F_{xx} \, + \, F_{xy} \big(- \, F_x \big) F_y \, – \, F_x F_{xy} F_y \, + \, F_x F_{yy} \Big(- \, \dfrac{F_x}{\cancel{F_y}} \cancel{F_y} \Big) }{\Big( F_y \Big)^3}$

Por lo tanto

$$\textcolor{BrickRed}{ {f’}’ (x) = \, – \; \dfrac{ F^2_y F_{xx} \, – \, 2 F_{xy} F_x F_y \, – \, F^2_x F_{yy} }{\Big( F_y \Big)^3}}$$

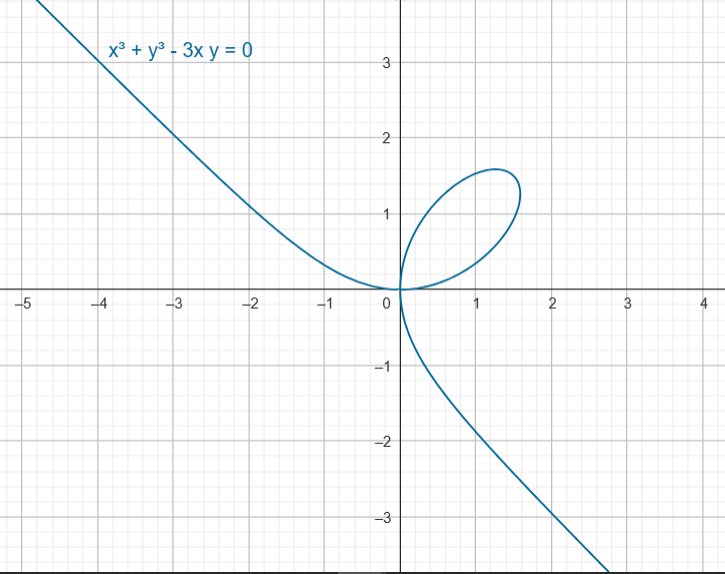

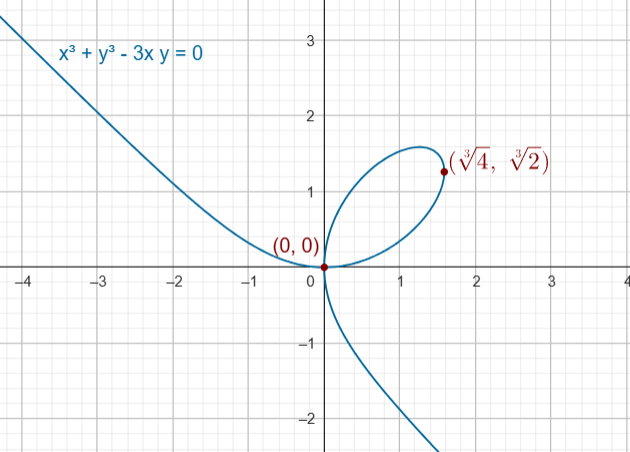

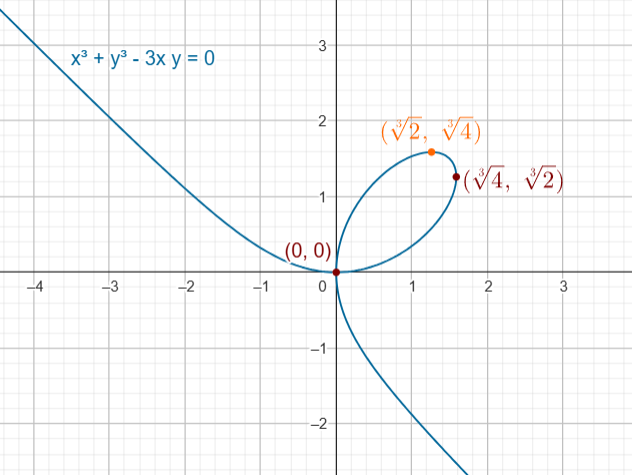

OTRO EJEMPLO

Dada $ F (x, y) = x^3 + y^3 \, – \, 3xy$

Consideremos $\mathcal{C} = \{ (x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \big| x^3 + y^3 \, – \, 3xy = 0 \}$

Calculamos sus derivadas parciales

$F_x = 3x^2 \, – \, 3y $

$F_y = 3y^2 \, – \, 3x $

Nos preguntamos, ¿en qué puntos podremos describir localmente a $\mathcal{C}$ como la gráfica de una función $ y = f (x)$?

Necesitamos que

$3y^2 \, – \, 3x \neq 0$

$ y^2 \, – \, x \neq 0$

Veamos cuáles puntos en $\mathcal{C}$ tales que $x^3 + y^3 \, – \, 3xy = 0 $. . . (1)

$\dfrac{\partial F}{\partial y} = 0 \; \iff \; y^2 = x$ . . . (2)

Sustituyendo (2) en (1)

$(y^2)^3 + y^3 \, – \, 3(y^2)y = 0 $

$y^6 + y^3 \, – \, 3 y^3 = 0$

$y^6 \, – \, 2 y^3 = 0$

$y^3 (y^3 \, – \, 2 ) = 0$

Entonces

Si $y^3 = 0 \rightarrow y = 0$ por lo tanto $ y^2 = x \rightarrow x = 0$. Luego el punto es el $(0, 0)$

Si $ y^3 \, – \, 2 = 0 \rightarrow y = \sqrt[3]{2} $ por lo tanto $ y^2 = x \rightarrow (\sqrt[3]{2})^2 = x \rightarrow x = \sqrt[3]{4}$. Luego el punto es el $(\sqrt[3]{4}, \sqrt[3]{2})$

Podemos encontrar las coordenadas del punto en la hoja del primer cuadrante que está a una altura máxima.

$ f’ (x) = 0 $

$ f’ (x) = \, – \, \dfrac{\dfrac{\partial F}{\partial x} (x, y) }{\dfrac{\partial F}{\partial y} (x, y) } = 0 \; \iff \; F_x (x, y) = 0$

Es decir, si $x^2 = y$, sustituyendo y despejando análogamente, se tendría que el punto es $(\sqrt[3]{2}, \sqrt[3]{4})$

${}$

OTRO EJEMPLO

Este ejemplo se abordó en una entrada anterior. Puedes revisarlo haciendo click en el enlace:

https://blog.nekomath.com/?p=101326&preview=true

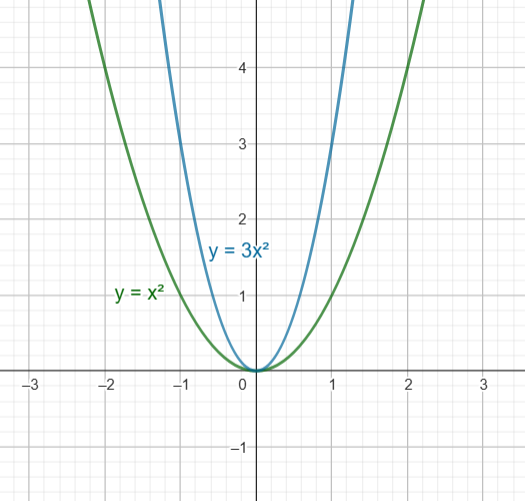

Sea $F (x, y) = (y \, – \, x^2 ) ( y \, – \, 3x^2)$

$\mathcal{C} = \{ (x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \big| (y \, – \, x^2 ) ( y \, – \, 3x^2) = 0 \}$

Calculemos las derivadas parciales:

$F_x (x, y) = \lim\limits_{x \to 0} \dfrac{F (x, 0) \, – \, F (0, 0)}{x} = \lim\limits_{x \to 0} \dfrac{3x^4}{x} = \lim\limits_{x \to 0} 3x^3 = 0$

$F_y (x, y) = \lim\limits_{y \to 0} \dfrac{F (0, y) \, – \, F (0, 0)}{y} = \lim\limits_{y \to 0} \dfrac{y^2}{y} = \lim\limits_{y \to 0} y = 0$

Por lo que el gradiente de la función es $ \nabla F (0, 0) = \vec{0}$ en el punto $(0, 0) \in \mathcal{C}$, por lo que no es posible aplicar el teorema.

${}$

En la siguiente entrada https://blog.nekomath.com/64-1-material-en-revision-teorema-de-la-funcion-implicita/ demostramos este teorema.